Why we're updating the minimum supported version of Postgres

As of Sourcegraph 3.27 (releasing on April 20, 2021), we're updating the minimum supported version of Postgres from 9.6 to 12.

If you are maintaining an external database and your Postgres version is older than Postgres 12, you will need to update your database instance prior to upgrading from Sourcegraph 3.26 to 3.27. See the following instructions for a step-by-step guide.

If you are using the Sourcegraph maintained Docker images, your instance is already using an appropriate Postgres version and no action is needed on your part.

Read the documentation guide for instructions on how to upgrade PostgreSQL.

Why does Sourcegraph 3.27 require Postgres 12?

Sourcegraph 3.27 requires support for new and old table references in statement-level triggers, but Postgres 9.6 contains an explicit SQL standard compatibility exclusion and does not support this. As noted in the documentation for creating triggers:

PostgreSQL does not allow the old and new tables to be referenced in statement-level triggers, i.e., the tables that contain all the old and/or new rows, which are referred to by the OLD TABLE and NEW TABLE clauses in the SQL standard.

We are requiring Postgres 12 because it supports new and old table references in statement-level triggers.

The rest of this post explains the technical motivation for why we needed this capability.

What are row-level and statement-level triggers?

In SQL, there are two ways a trigger can be executed:

- Before or after a row is inserted into/updated within/deleted from a target table

- Before or after an insert, update, or delete statement over a target table

In the former case, the trigger has access to the OLD and NEW row values, which allows values of particular columns to be used within the trigger.

In the latter case, the trigger does not have access to the previous or the updated data. Unfortunately, statement-level triggers have no access to previous data, and must re-query the target table to make use of any newly updated data.

Why do we need statement-level triggers?

Sourcegraph performs database migrations on application startup. We try our best to keep these migrations fast, as a slow migration will block additional container instances from starting and accepting traffic.

Some classes of migrations are very difficult to do efficiently:

- Index creation over large tables requires a full table lock

- Concurrent index creation cannot be applied within a transaction

- Concurrent index creation takes much longer, can be blocked for an arbitrary amount of time due to live transactions, and can fail requiring an operator to rebuild the index (cherry on top: reindex is not concurrent)

- Data migrations over large tables can take an arbitrary amount of time

Sourcegraph 3.25 introduced a mechanism for performing out-of-band migrations. Instead of being applied synchronously on application startup, out-of-band migrations are applied in the application background over a longer period of time.

Each migration is written in a generic way that allows it to be controlled by a global migration runner. This runner is responsible for controlling the throughput of the migration so that it does not require disproportionate memory or compute resources in the database or in the application.

Each migration is required to report its own progress (0-100%) to aid the runner in determining the set of migrations which need to run (and in which direction they must run in the presence of downgrades).

We ran into problems with Postgres 9.6 triggers when trying to implement an out-of-band migration to re-encode the way code intelligence data is stored. A few tables in the codeintel database stores gob-encoded payloads in a bytea column. In order to migrate this data into another shape, we need to read these payloads in batches, perform the data migration over each row (in Go, which can properly decode/re-encode the data), and then write the new payloads back to the database.

We chose to add a version column to these tables so that the backend can determine how to properly interpret the payload of a particular row. This way, both old and new payload shapes can be read while new rows are written with the new shape, and old rows are eventually rewritten into the new shape.

This is where the tradeoffs come in to play.

In our Cloud environment, the lsif_data_definitions table contains around 300 million rows. Simply counting the number of rows takes around 24 minutes on our production database instance, as seen by the following (simplified) query plan:

Finalize Aggregate

-> Gather

Workers Planned: 2

Workers Launched: 2

-> Partial Aggregate

-> Parallel Index Only Scan using lsif_data_definitions_pkey on lsif_data_definitions

Heap Fetches: 14939021

Planning Time: 1.241 ms

Execution Time: 1442409.435 ms

(9 rows)Postgres requires that each returned row be visible to the current transaction as a way to prevent serving phantom data that was deleted by a previous query. Unfortunately, row visibility information is not stored in the index, but in the heap entry for the row.

As explained in the documentation for index-only scans, partially visible pages require a heap access to check which rows are visible and which are not. These heap access and visibility checks dominate the running time of this query.

Speeding up counting queries

A near half-hour query is not efficient. Due to the consequences caused by Postgres MVCC, there are few actions under our control that could make a count of so many objects faster. Instead, we should count fewer things.

In our naïve attempt to determine the progress of a particular migration, we wanted to simply report the ratio between the number of rows with a version above our target and the total number of rows in the table. However, we don't need progress reporting to be completely accurate (except for at the 0% and 100% edges).

Each table we care to migrate in the codeintel database has a composite primary key containing an index identifier. Each unique index identifier corresponds to a precise code intelligence index file uploaded by a user.

Instead of counting the ratio between migrated rows and total rows (which is very large), we can instead count the ratio between migrated indexes and total indexes (which is orders of magnitude smaller - 300 million vs. 23 thousand).

The obvious approach would be to migrate all rows in a table associated with the same index at once. Unfortunately, indexes can be very massive. Some large customers are regularly uploading 13GB index files. Thus, our migration batch size is likely going to be too small to guarantee all rows can be migrated, and increasing the batch size will add additional memory and compute constraints on the migrating container.

The approach we chose tracks the minimum and maximum row versions for each index in a separate, much smaller table.

lsif_data_definitions:

| index_id | scheme | identifier | data | version |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | foo | bar | .... | 1 |

| 1 | bar | baz | .... | 2 |

| 2 | baz | quux | .... | 2 |

| 2 | quux | bonk | .... | 2 |

| 3 | bonk | honk | .... | 1 |

lsif_data_definitions_schema_versions:

| index_id | min_version | max_version |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 1 |

This second table allows us to efficiently determine which indexes have been migrated and which still need attention. For example, if we are currently migrating from schema version 1 to 2, then the table above shows index 1 is partially migrated, index 2 is fully migrated, and index 3 has yet to be touched.

It is an efficient operation to count both the total number of indexes as well as the number of indexes that are above or below a particular schema version.

The schema version bounds can be kept in sync with the source table trivially by using triggers on inserts, updates, and deletes: if we insert a new row with a new lowest or new highest version or if we update/delete a row with the last remaining lowest or highest version, then we update the associated minimum or maximum version for that index.

Analyzing the trade-offs

Engineering performance around a database is full of trade-offs. In this case, we've gained faster counts by sacrificing efficiency of inserts.

After processing a precise code intelligence index file, we insert data in Postgres utilizing very large bulk insert operations. During this process, we insert tens to hundreds of thousands of rows over multiple tables for each index, but we don't make tens of thousands of requests. As of this post, our Cloud environment has a single precise code intelligence index with ~390k rows in the definitions table alone. Each precise code intelligence index has over 12k rows in this table on average.

For each insertion query, we supply as many rows as possible (Postgres has a limit of 65535 values per query). This reduces the total number of round trips to the database, but also minimizes the number of total queries (and invocations of statement-level triggers).

We are unable to utilize a statement-level trigger approach in Postgres 9.6 as such triggers would not know the value of the index_id or version columns of newly inserted rows. This leaves us with row-level triggers only, and such an approach would double the number of writes to the database: for each row inserted in the target table there is another upsert to the schema versions table.

So how bad would this approach be?

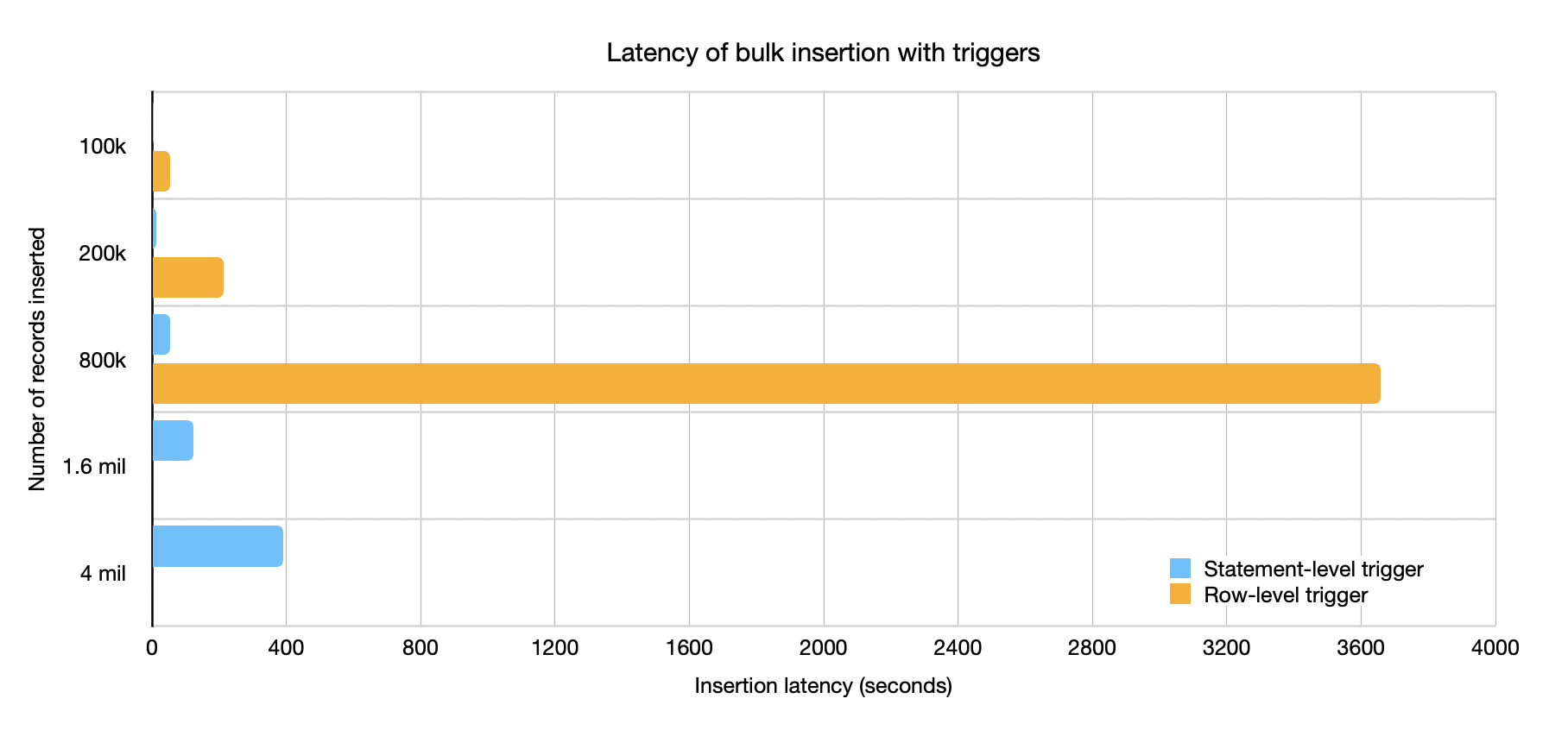

Turns out it's pretty bad. Inserting 800k rows into the database with statement-level triggers takes under a minute (on a non-production test machine). Using row-level triggers the same operation takes over an hour.

Conclusion

In order to enable us to continue to scale and improve the performance of your Sourcegraph instance, we are bumping the minimum supported version of Postgres to unlock new features and performance enhancements.

Once you plan to upgrade to Sourcegraph 3.27, you must first ensure that your database meets the new minimum version requirement of Postgres 12. See the following instructions for a step-by-step guide.