Strange Loop 2019 - Federated learning: private distributed ML

Overview

This talk will explain the ideas around training models on different nodes in more detail. I'll describe a specific instance of a federated learning algorithm (called federated averaging), and I'll explain the ways in which the real world full of malicious actors and distributed systems complicates the naive picture. I'll then talk about the research that is going on right now to harden security, reduce communication costs, and strengthen privacy guarantees.

Mike started his talk on Federated Learning by sharing that this topic has renewed his interest & optimism for machine learning because it gets around issues like privacy. In his view, federated learning combines areas like distributed systems, AI, differential privacy, homomorphic encryption, etc.

Machine Learning

ML is the field of algorithms that infer rules connecting data to answers, given data & the right answers. It differs from classical programming by infering the rules instead of explicitly being provided with a set of rules.

The most common machine learning workflow involves moving data from different sources to one location. This gives rise to the issue of privacy. If you use products built by various large tech companies, you invariably end up handing over your private data to them which they use to train their models.

Relatedly, due to restrictions like GDPR in the EU, companies are restricted in the types of data they can collect, so a machine learning approach that eliminates the need for data to be transferred out of customer devices to corporations becomes necessary. Mike also refers to this talk and explains that collecting data that isn't needed often leads to larger engineering problems and does not necessarily provide value. At the very least you can incur high storage costs or accidentally leak the data, putting your customers' privacy at risk.

Federated Learning

Here's the setup: we have training data for our machine learning experiment distributed across many different nodes (computers or mobile devices). But training the model requires all the data be transferred to a central location. We want to avoid moving all this data and training on all of it centrally.

Mike explains the Federated Averaging algorithm which first appeared in a paper in 1990. It's a very simple algorithm so it's surprising that it works well.

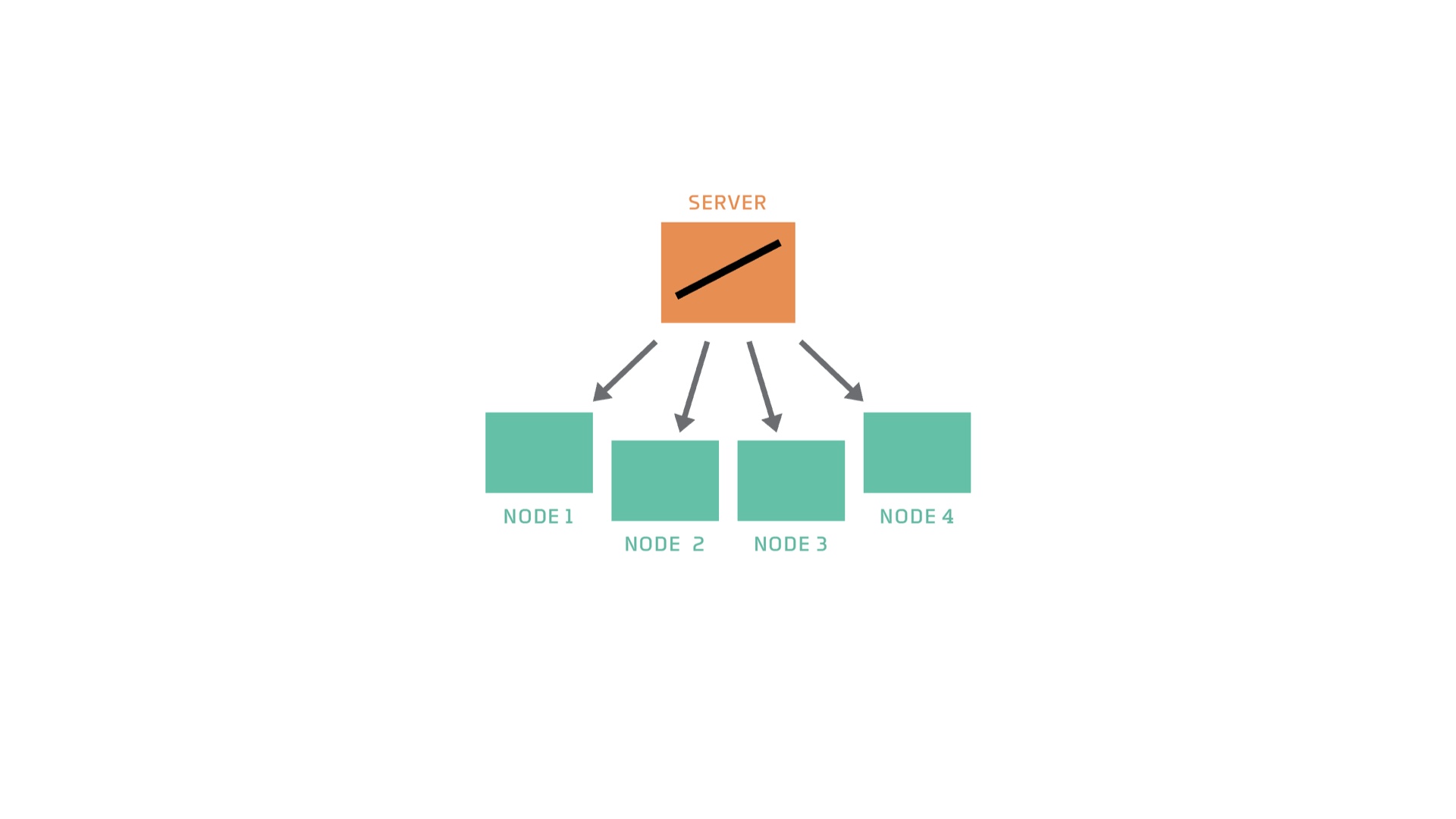

In the diagram above, we have a server and 4 nodes. The server has a model, imagine something simple like an SVM or linear model. The server starts by copying over the model to all of the nodes. This means two things - we're going to train this model and each node should train it with its own data. Each node starts training the model incrementally with the data that's available to it (locally or by acquiring it). A common way that many machine learning algorithms perform training is through gradient descent. Each node trains its model so that it is better than the copy it received from the server. Once the nodes finish training their models, they send them to the server. The algorithm is named Federated Averaging because of this next step. When the server receives models from each of its nodes, it averages over all the models and stores that average as a representation of the data on all the nodes. This is one round of federated averaging. We repeat this whole process for as long as we want, so that the models are constantly improving.

As you probably noticed, we do not transfer any data to the server in this whole process. Additionally, we also probably used less power and bandwidth to transfer the model itself.

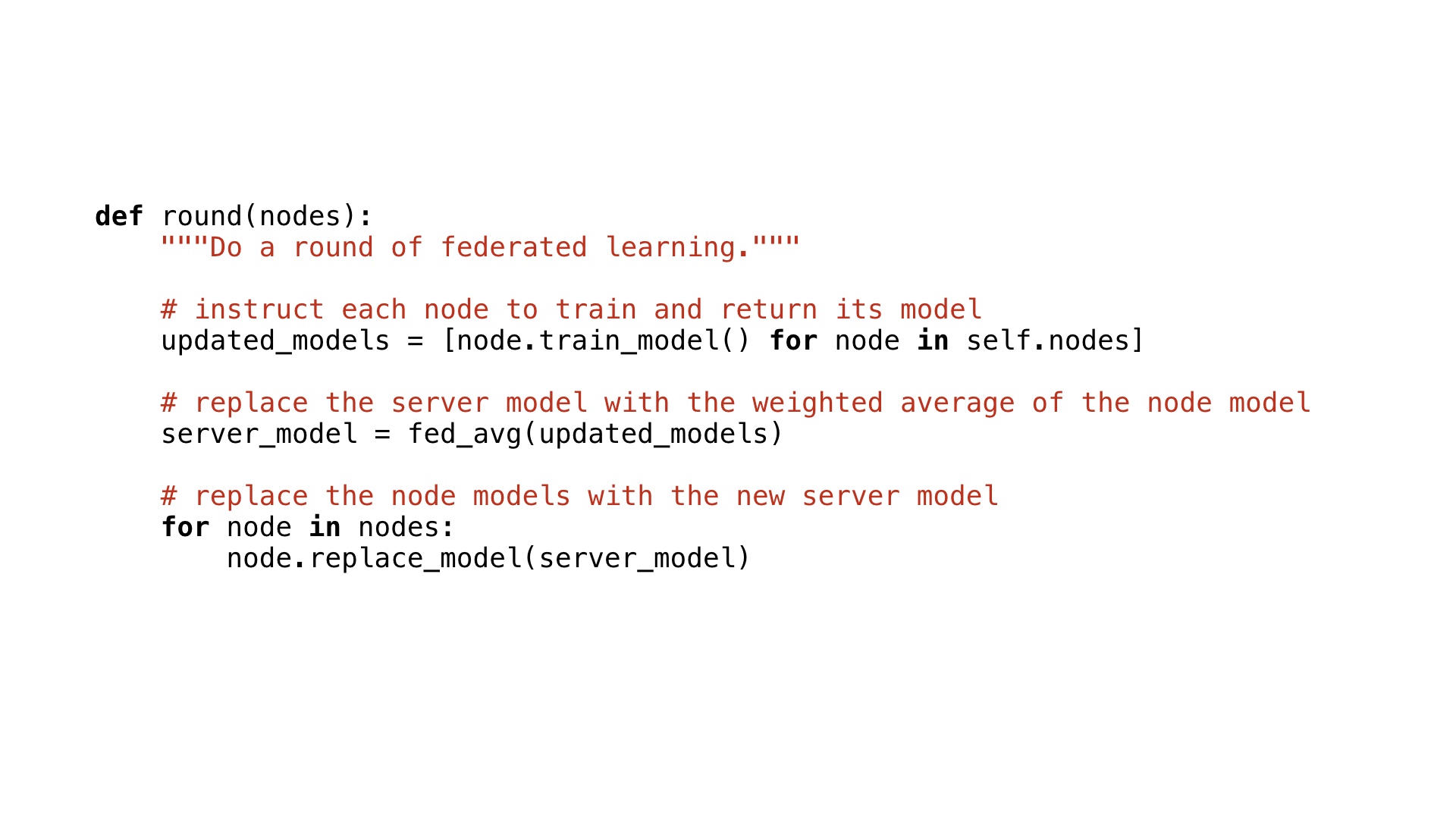

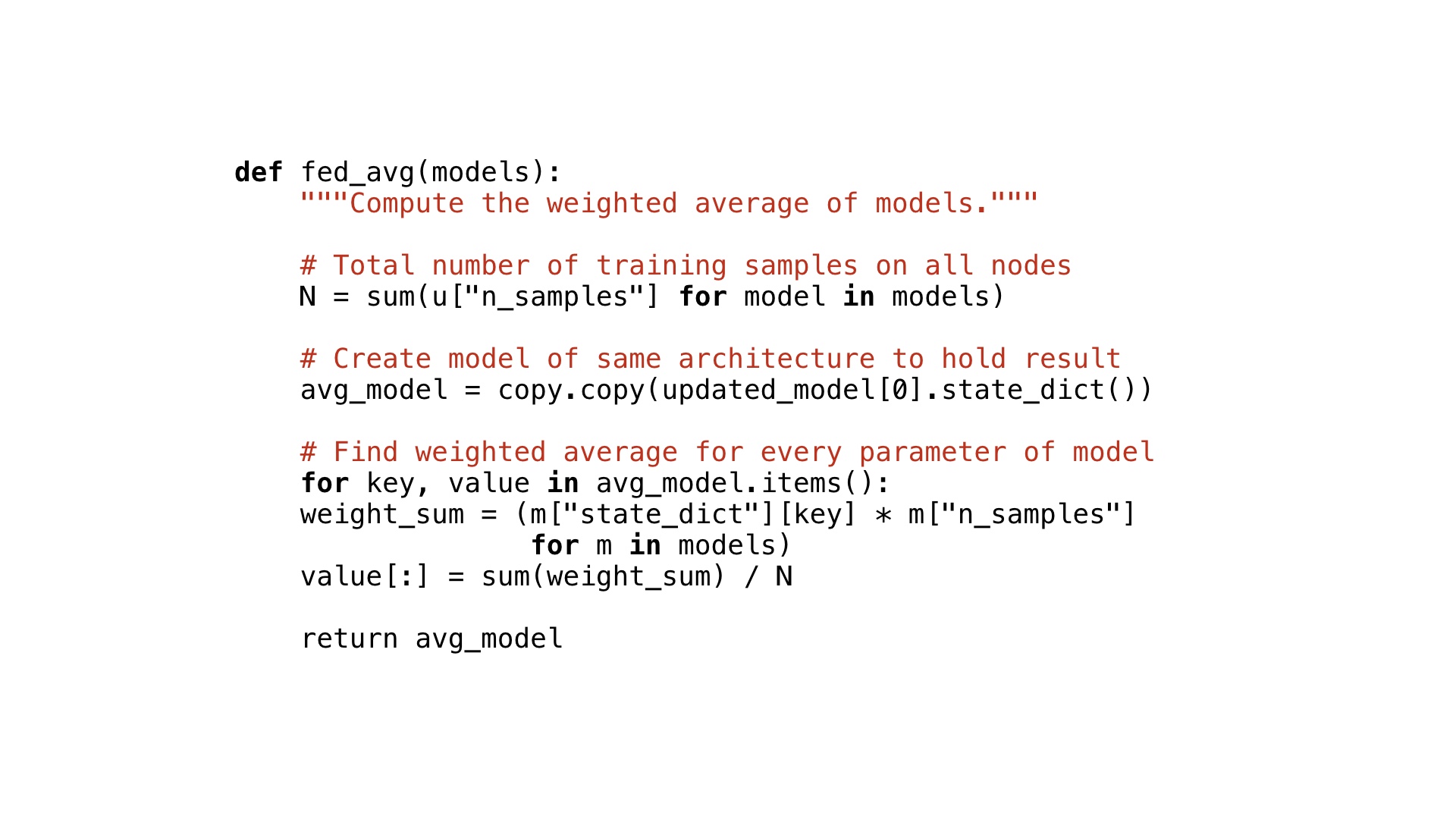

Here's how that looks in pseudocode -

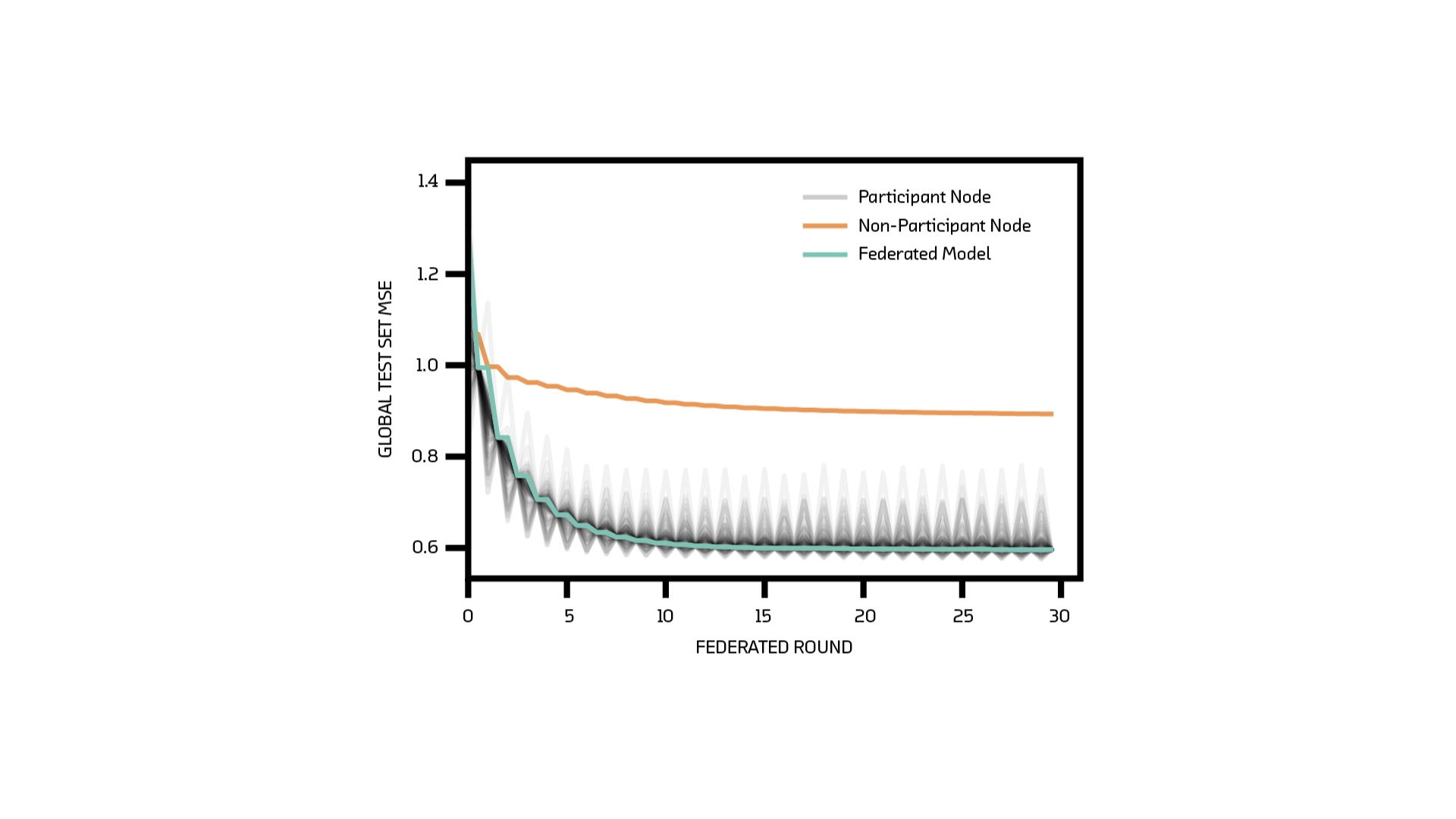

The loss curve for the above algorithm looks like this.

The grey lines are the model on each node. They get better (or worse) during a round because they’re learning the peculiarities of a small set of data, which may or may not generalize to the test set.

The orange line is from a node that trains just as often but refuses to communicate with the server. It gets better as well but not by much because overall, it's been trained on much less data. The green line is the one we care about - we can see that it improves without transferring any data.

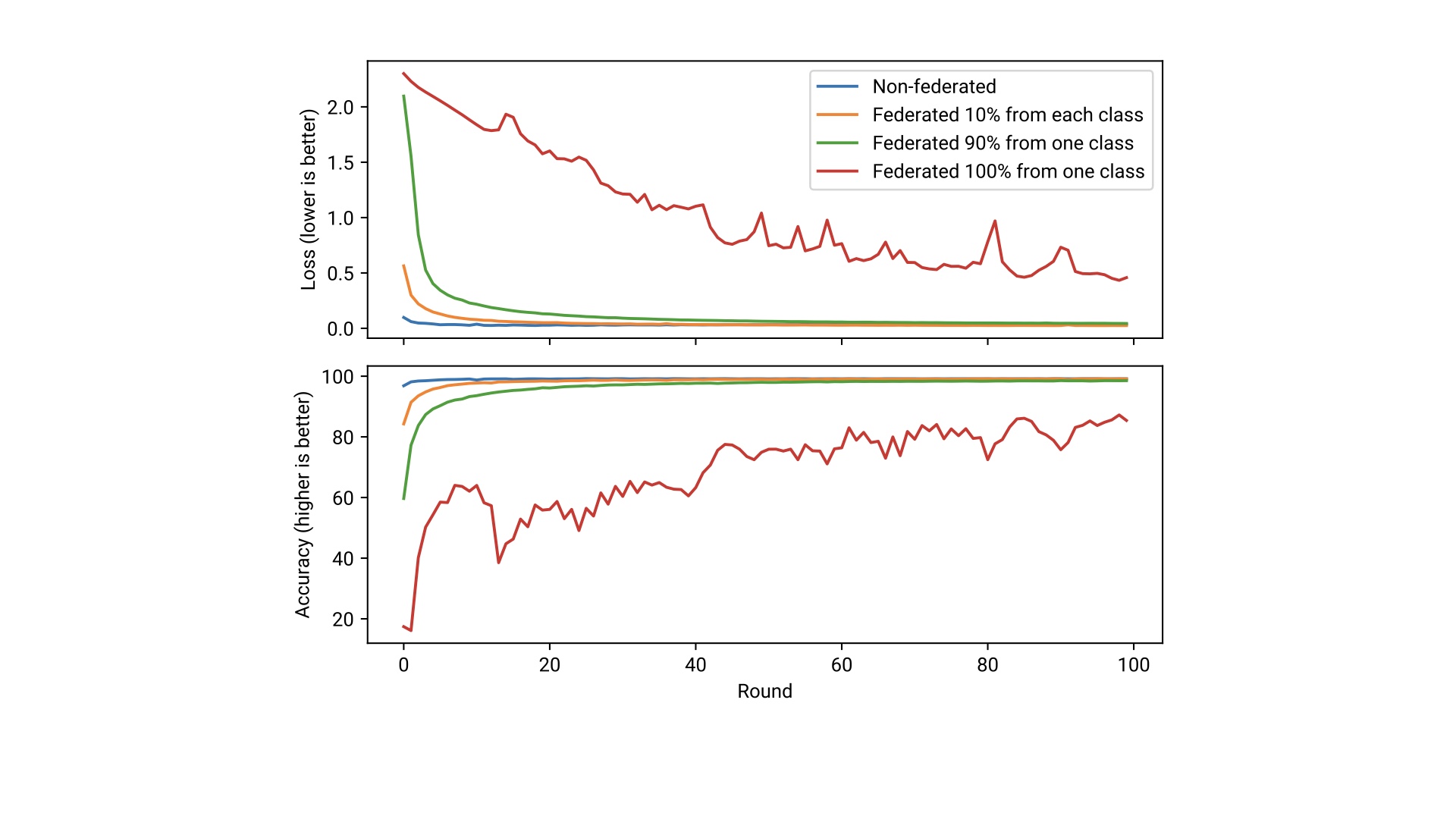

We can use the same algorithm on the MNIST dataset containing 10 classes. Instead of assuming that we'd have a balanced dataset like MNIST, we consider 4 different cases where the data distribution is skewed on each node.

These can be described as -

- Non-federated: all data is used for training

- Uniform on each node: each node has a well-balanced distribution of data from each class

- 90% of one class on each node: each node's samples are mostly from one class with a few samples from other classes

- 100% of one class on each node: each node has samples only from one class.

Now, training the model using federated averaging on each of the 4 distributions yields a graph like this -

We can see that federated averaging reaches perfect accuracy more slowly but even on highly biased data (90% of one class, 10% of the others) performs fairly well. The case in which we only have data from one class on each node also does well - though accuracy is not perfect, Mike said that it would have improved over subsequent runs; also this accuracy is better than chance. Overall, we can see that this simple algorithm has a lot of potential.

Challenges

- How do we know if it works?

We do compare our models by training in the non-federated way and demonstrating that the federated version does atleast as well if not better. It's possible to prove this works for linear models and some special cases but not in other cases.

- Resource consumption

Even though we aren't transferring data, this is a heavy workload for a phone. Mike mentions that one paper presents an algorithm which would communicate an updated model only when it reaches a certain threshold of difference from the original model. Tweaks like this could improve overall bandwidth usage & power consumption.

- Distributed systems land

We need to be robust to many failure modes! Vanilla federated averaging is not robust. The training round would not complete until the slowest node in the network finishes & if you don't handle the case where a node fails, it might be a bigger problem.

- Privacy

It's not impossible to infer the attributes of training data from a trained model. Mike presented one example from a paper on GANs which showed that a node in a network could reconstruct an image from the original training dataset.

Some ways to mitigate the attacks on privacy would be homomorphic encryption and secure aggregation. Homomorphic aggregation involves encrypting the model updates such that the server can still apply algebraic operations to them but they don't need to be transferred in plain text. This is expensive but can be implemented since the burden would be on the server and not relatively less powerful phones & other devices.

The other mitigation is differential privacy which basically is a way to share information about datasets by describing the group and withholding information about individuals.

When should you consider Federated Learning?

Since federated learning introduces complexity by way of distributed systems, it's important to make sure you have a good usecase for it. If the data is distributed and you care about privacy or system resources like power, bandwidth, etc then federated learning might help.

Mike cautions against applying federated learning until you've established performance benchmarks and demonstrated that you could do better than that benchmark with more training data. PySyft is a mature library for trying out federated learning and so is TF-Federated if you use Tensorflow.

Referenced Material