How Caddy auto-detects HTTPS interception

Matt Holt

Matt Holt is the creator of the popular Caddy Web Server.

Caddy is called what it is because it acts like a compartment for all your server things. Most people use its HTTP server, but Caddy can also serve DNS, and there are a number of other plugins that extend Caddy’s functionality.

Caddy is the HTTP/2 web server with automatic HTTPS. (New logo shown.)

Pluggable servers benefit both you (the developer) and all the people who use your site/service. You get a single, consistent interface with which to configure your server(s), and your visitors enjoy (without realizing it) the sensible, secure defaults programmed into Caddy. In fact, Caddy’s signature advantage is its TLS stack, which is designed for HTTPS but can work with any other server type. Powered by the Go standard library’s robust crypto/tls package, Caddy takes full advantage of everything from modern cipher suites to side channel protection and memory safety.

But the standard library doesn't always export the functions you need. In this post, I’ll explain what my process was for implementing an unusual new feature in Caddy that involved hooking into some of the standard library’s un-exported codebase. Specifically, we’ll be looking at the new mitm.go file.

(The technical/design solutions here were not all my own work. This feature is based on a paper. I also had help from the Gophers Slack, Go Forum, and Filippo Valsorda. It’s always great to learn from programmers more brilliant than yourself!)

Defending Privacy: The Web Server’s Role

A recent publication described a technique for HTTPS servers to detect when a TLS connection is being intercepted (MITM by TLS proxies). Interception is common behavior with antivirus and enterprise firewall software, and they often break things and slow the adoption of new versions of TLS.

Although the heuristics we use aren’t always perfect, this feature has obvious value: expose potential censorship or malware, and warn users of the breach in their privacy.

The idea is simple. It involves comparing the HTTP User-Agent header to the characteristics of the TLS ClientHello of the underlying connection. If the browser indicated by the User-Agent does not emit a ClientHello like the one seen for that connection, the connection is likely being intercepted. (Research shows that TLS proxies — benevolent or otherwise — are often careless about the client’s protocol preferences, and that nearly every browser and proxy has a unique fingerprint from the ClientHello alone.)

The web server is in a unique position to detect these anomalies where the client is not able to. I figure Caddy should be able to do this and let the site owner decide how to handle the connection in that situation: log the event, redirect to an informational page, or inject a warning into the web page directly so the user can be informed that their connection is not private, despite any green lock in the browser. Caddy is, so far, the only web server to provide this feature (soon to be released).

Technical Problems

Aside from the difficulty of getting the heuristics just right, there are a few issues specific to Caddy and Go that make this a non-trivial feature.

Go’s net/http Handlers do not expose the underlying connection at all. This makes it difficult to match an http.Request to the net.Conn and thus the TLS ClientHello, which we need to compare against the User-Agent header at request time. How do we map requests to connections?

Even if we could access the ClientHello, we need to get very specific information from it. Go 1.8 now has a GetConfigForClient callback that makes the ClientHelloInfo struct available (a struct which has more fields as of Go 1.8), but the information in that struct is not sufficient for executing the heuristics. We need the raw ClientHello bytes. How do we get the raw bytes?

In order to get the raw ClientHello, we need to read it in ourselves. But these functions are deep in the crypto/tls package, un-exported. Copying mature security code out of its source and modifying it is a bad idea. How do we correctly and efficiently read part of a TLS handshake without duplicating the standard library?

Technical Solutions

Fortunately, there are acceptable solutions to all these problems.

Mapping Requests to Connections

I could not find a reasonable way to map HTTP requests to their underlying connections without using a map shared by all the connections on the listener.

What will the map key be? It has to be something exposed to both the net.Conn and the http.Handler. That rules out the pointer to the net.Conn itself, as http.Request does not expose that. But each connection should be served on a unique client IP and port. This works! We use net.Conn.RemoteAddr().String() down at the connection level and http.Request.RemoteAddr up at the request level. This means our key will be a string. The value type will be a struct that stores the information we collect from the ClientHello.

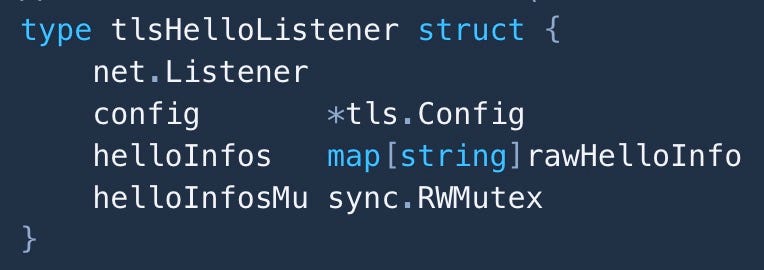

We then create a custom listener that holds this map and a mutex to synchronize it (and a few other necessities):

This type embeds the standard TCP listener, so all its functionality is automatically promoted to our tlsHelloListener. Yay! We just make one of these for our server instead of calling tls.NewListener().

After answering the next question, you’ll see why, and we should be close to accessing the rawHelloInfo from the HTTP hander.

Getting Access to the Raw ClientHello Bytes

With our own listener, we’re close to accessing the raw bytes from the wire.

Somehow we need to read bytes from the network without consuming them exclusively, or else we need to perform the entire TLS handshake ourselves. No thanks. So, buffering it is. Fortunately, the ClientHello is the first message of a TLS handshake (preceded only by a short 5-byte header).

We could implement our own Accept() method which reads the bytes we need before returning with the underlying Accept(). But don’t forget— Accept() is a blocking call in the HTTP server loop. Never read from the network in the same goroutine as the server’s Accept() loop; you won’t be able to accept new connections until you've finished reading from the previous one! That is bad, even for just a few hundred bytes.

What’s the alternative? We can’t block on Accept(), but there's a function that’s specifically for reading from the network, and it runs in its own goroutine: net.Conn.Read(). So I implemented my own “wrapper” over the standard net.Conn type:

type clientHelloConn struct {

net.Conn

listener *tlsHelloListener

readHello bool

buf *bytes.Buffer

}We have it keep a reference to the listener so it can store the parsed data in the map.

Back to the tlsHelloListener for a moment. Right now, it acts like the plain TCP listener embedded inside it. We need to make it act like a TLS listener:

func (l *tlsHelloListener) Accept() (net.Conn, error) {

conn, err := l.Listener.Accept()

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

helloConn := &clientHelloConn{

Conn: conn,

listener: l,

buf: new(bytes.Buffer),

}

return tls.Server(helloConn, l.config), nil

}Ah, much better! No blocking, and we can still hook into the connection by implementing Read() on our clientHelloConn.

Reading the Raw ClientHello Bytes Off the Wire

This is tricky. Not only are we dealing with highly volatile network environments, but these are also TLS connections, which are highly sensitive to mistakes.

The first iteration of our Read() is a simple pass-thru that doesn't do anything custom:

func (c *clientHelloConn) Read(b []byte) (n int, err error) {

return c.Conn.Read(b)

}Booorrrring. So what do we know? We know that we need to read the ClientHello if it hasn’t already been read. But if it has, our job is done, and it can carry on as if we weren't there:

func (c *clientHelloConn) Read(b []byte) (n int, err error) {

if c.readHello {

return c.Conn.Read(b)

}

// TODO: read the ClientHello

}We can replace our TODO with some code to read the header:

hdr := make([]byte, 5)

n, err = io.ReadFull(c.Conn, hdr)

if err != nil {

return

}From this header we get the length of the ClientHello and can read that many bytes. Put this into an io.MultiReader for the standard lib to do the rest. Done.

Easy, right? Danger, danger! We are reading bytes from an untrusted client for a sensitive protocol that impacts the security of the rest of the connection. Is this a real connection or an attack? What about timeouts/deadlines? What about all the edge cases that the standard library handles, like clients that don’t speak TLS or malicious handshake records? We’re asking for trouble trying to do this ourselves and assuming that the client is virtuous.

So scratch that ReadFull()code above. We’re going to let the standard library do all the reading from the wire and we’ll mooch on what it gets for us. It will take care of timeouts and most edge cases, drastically reducing the error surface. What the standard lib reads in, we will have copied to our little buffer:

tee := io.TeeReader(c.Conn, c.buf)

n, err = tee.Read(b) // standard lib does the dangerous stuff!

if err != nil {

return

}

if c.buf.Len() < 5 {

return

}Above, we check that we have 5 bytes for the header. Once we have that, we’ll inspect it to get the length of the ClientHello. We’ll make sure the length is a reasonable value and then read the rest of the ClientHello using the same kind of code, which I’ll skip here for brevity, but you can read it at the source.

Parsing the ClientHello Manually

I borrowed (with credit) some code from the standard library to parse the ClientHello record. Fortunately, it’s mostly a single function that is pretty straightforward, and I only needed a subset of the full ClientHello. Still, I cross-referenced dozens of other areas in the standard library and Sourcegraph was an invaluable tool for clicking around, checking definitions, etc.

After we’ve parsed the ClientHello and stored the results in the map, we can clear the buffer and indicate that we’re done:

c.buf = nil

c.readHello = true

returnThe HTTP Handler

To bring this full circle, the last piece of the puzzle was to create an HTTP handler that could read from that map. The most conventional way of doing this is writing an HTTP middleware with a reference to our tlsHelloListener:

type tlsHandler struct {

next http.Handler

listener *tlsHelloListener

}Its ServeHTTP() method looks something like this:

func (h *tlsHandler) ServeHTTP(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

if h.listener == nil {

h.next.ServeHTTP(w, r)

return

}

h.listener.helloInfosMu.RLock()

info := h.listener.helloInfos[r.RemoteAddr]

h.listener.helloInfosMu.RUnlock()

// (do things, then call next.ServeHTTP)

}The locking is unfortunate, but load tests with wrk indicated no noticeable performance degradation.

Conclusion

Phew! I hope you enjoyed this. But I’ll bet I had more fun coding it up than you did reading this. (The proof is in the code!)

Is this solution perfect? Nope, it does involve a slight bit of buffering and locking (again, nothing too bad), and my implementation may still have flaws (bug reports welcome) — but thanks to Go’s design and use of interfaces, this task wasn’t painful. You just have to be creative without being too clever!

You can try Caddy’s MITM detection feature now by building Caddy from source using Go 1.8. Basic instructions are included with the pull request.