GraphQL: Client-Driven Development

@beyang

Dan Schafer (@dlschafer) is the co-creator of GraphQL and works as a software engineer at Facebook. He spent 2 years on the Newsfeed team before he joined the team that would eventually create GraphQL.

Today, he's talking about some of the fundamental characteristics of GraphQL and how they evolved. It didn't just emerge from the primordial void. There was a lot of discussion and evolution over the course of it history.

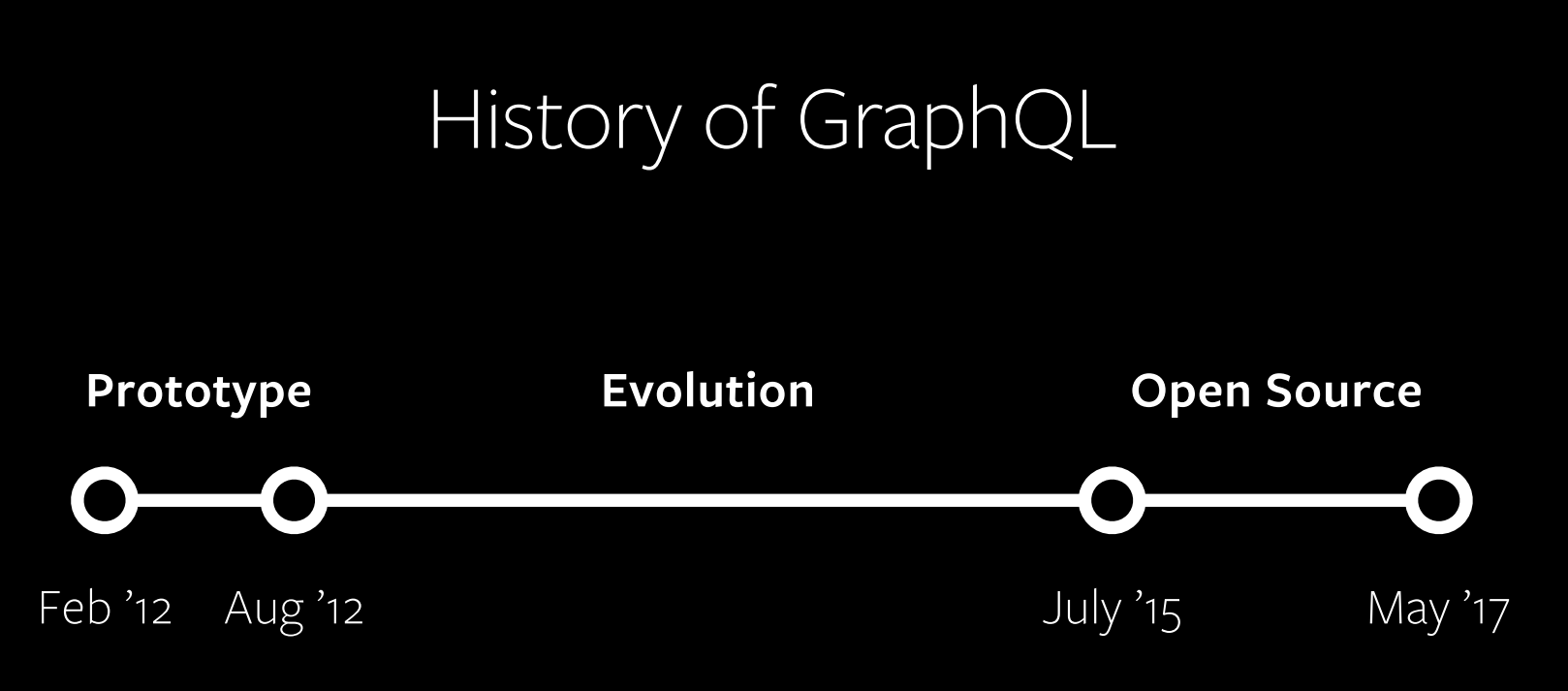

A bit of history: GraphQL was first publicly described in May of 2015 in a blog post elaborating on Relay, Facebook's framework for structuring data flow in React Apps, which itself had been published in January of that year.

From the get-go, GraphQL took a product-centric viewopint, It is "unapologetically driven by the requirements of views and the front-end engineers that write them." The GraphQL "starts with their way of thinking and requirements and build the language and runtime necessary to enable that."

The prototyping phase

GraphQL started with a few core ideas in mind:

- Think "Graphs", not "Endpoints"

- Have a Single Source of Truth

- Thin API Layer

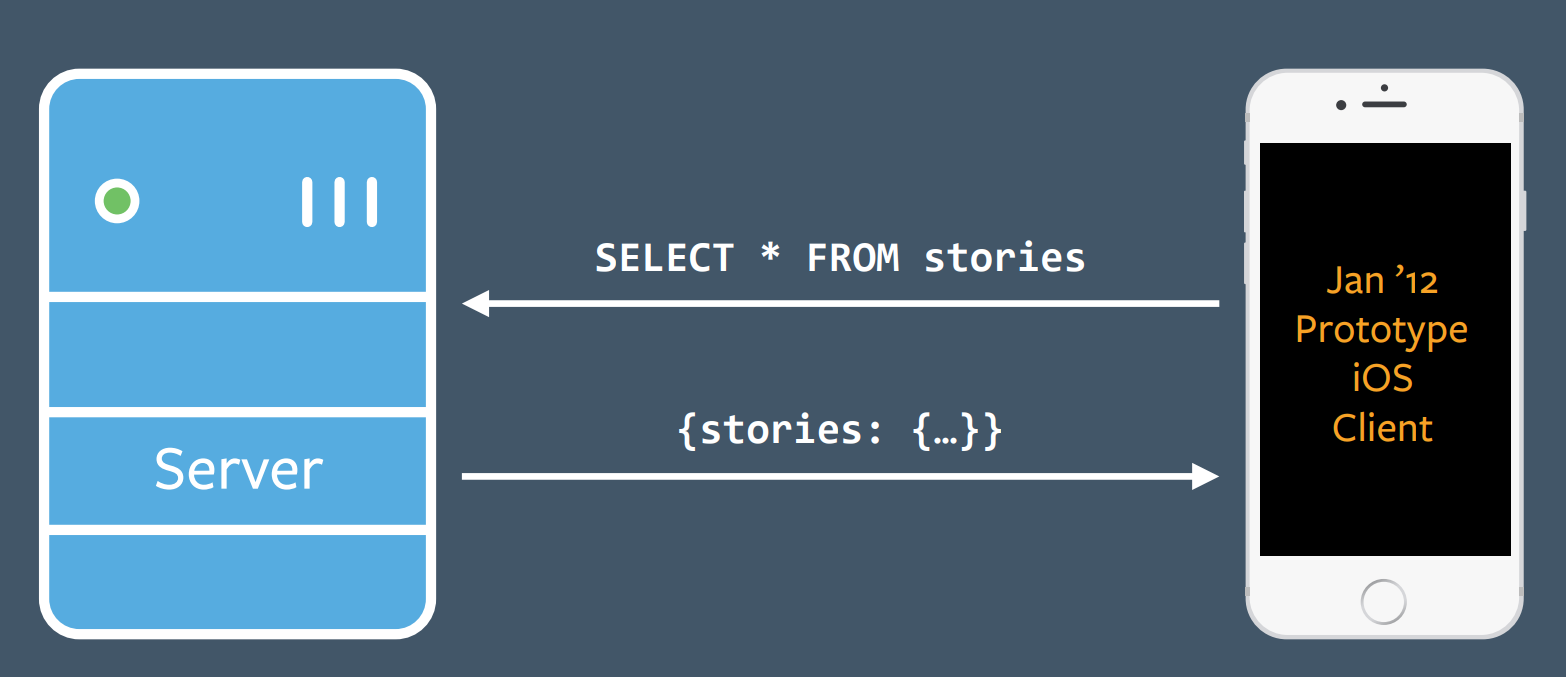

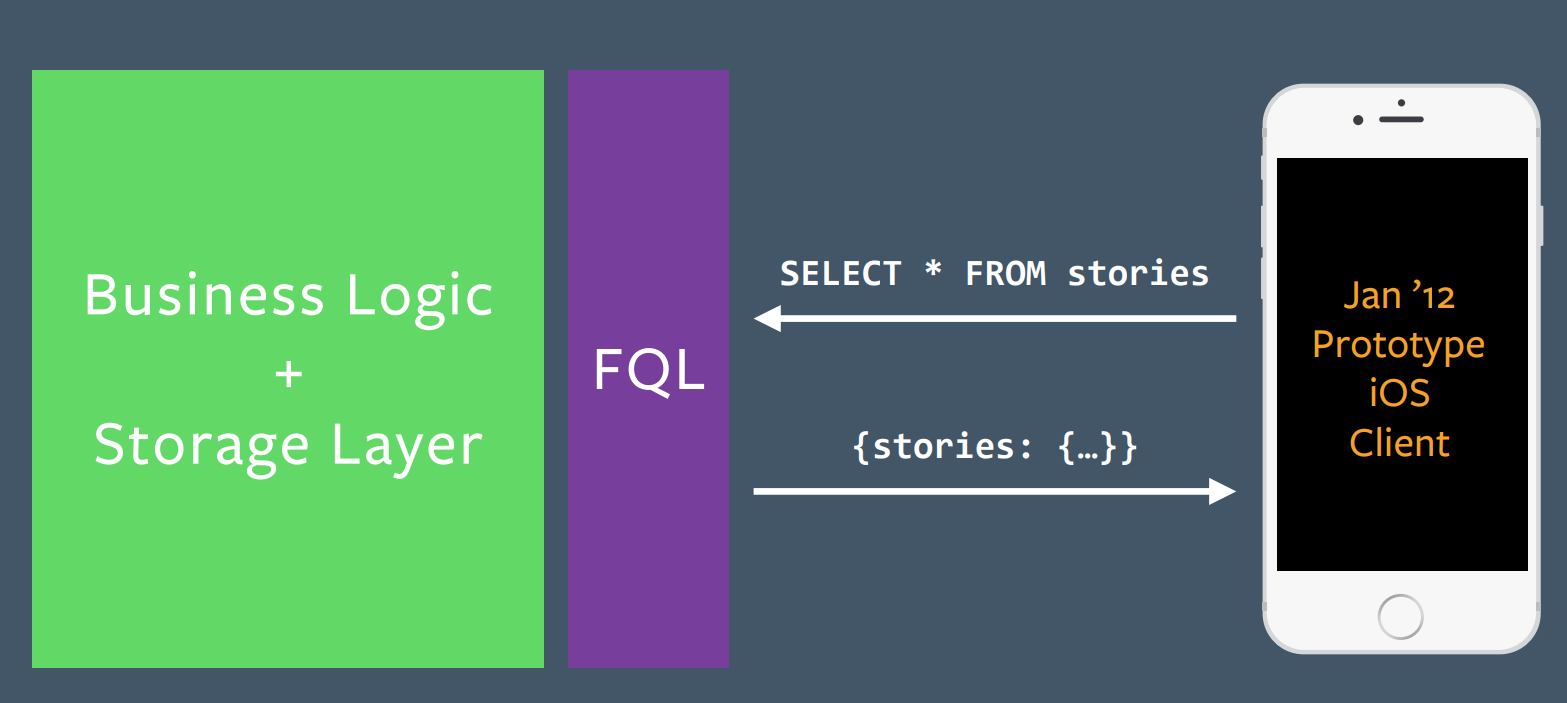

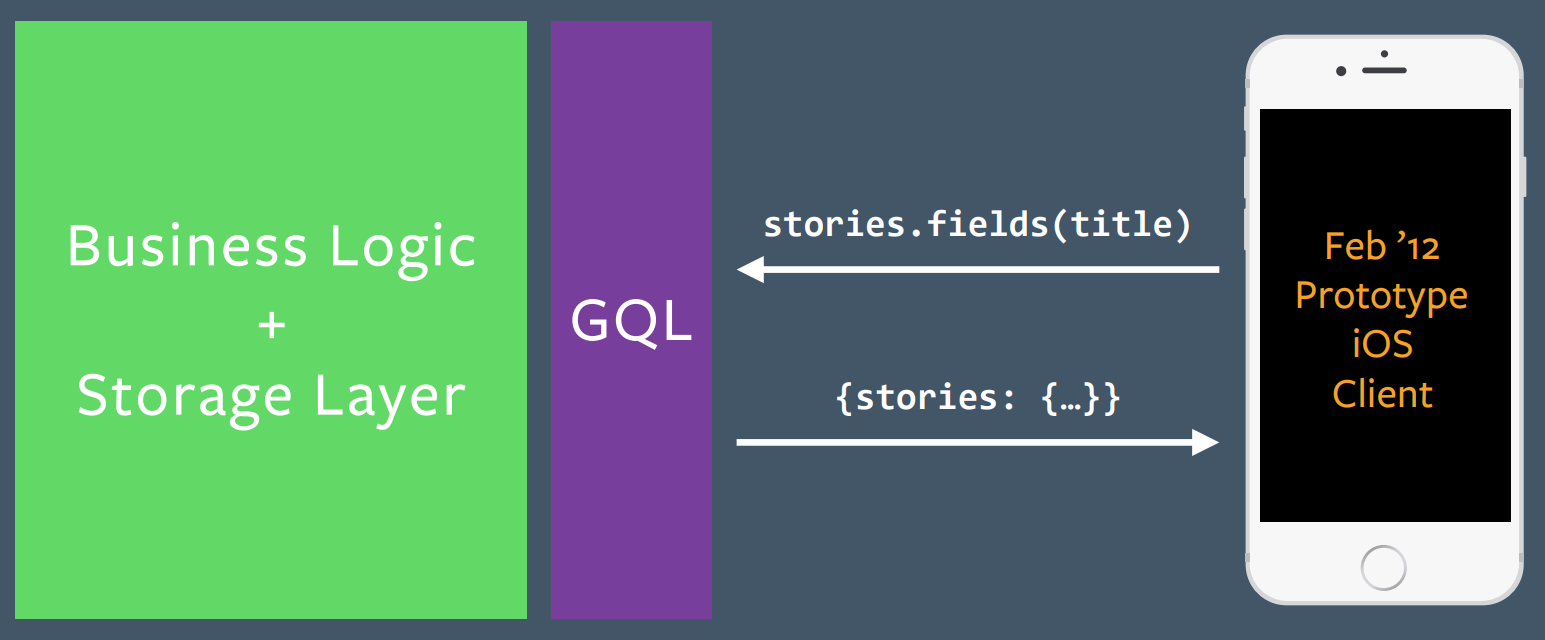

The initial end-user application target of GraphQL was the Facebook iOS client. At the time the new prototype client was built, its backend was still using FQL (Facebook Query Language), which accepted SQL directly from the frontend as its query language. Frontend developers were not happy with this situation.

In about a month of prototyping, the team replaced the FQL layer with GraphQL.

He emphasizes that the GraphQL team was really driven by client needs. No one woke up and said, "Hey, we should change GraphQL." They were driven by feedback from the frontend developers whose needs they were addressing.

The evolution phase

He'll talk about 3 developments that were driven by client needs.

- Scaling models

- Scaling views

- Scaling updates

Scaling models

query {

me {

name

nickname

profilePicture {

width

height

url

}

}

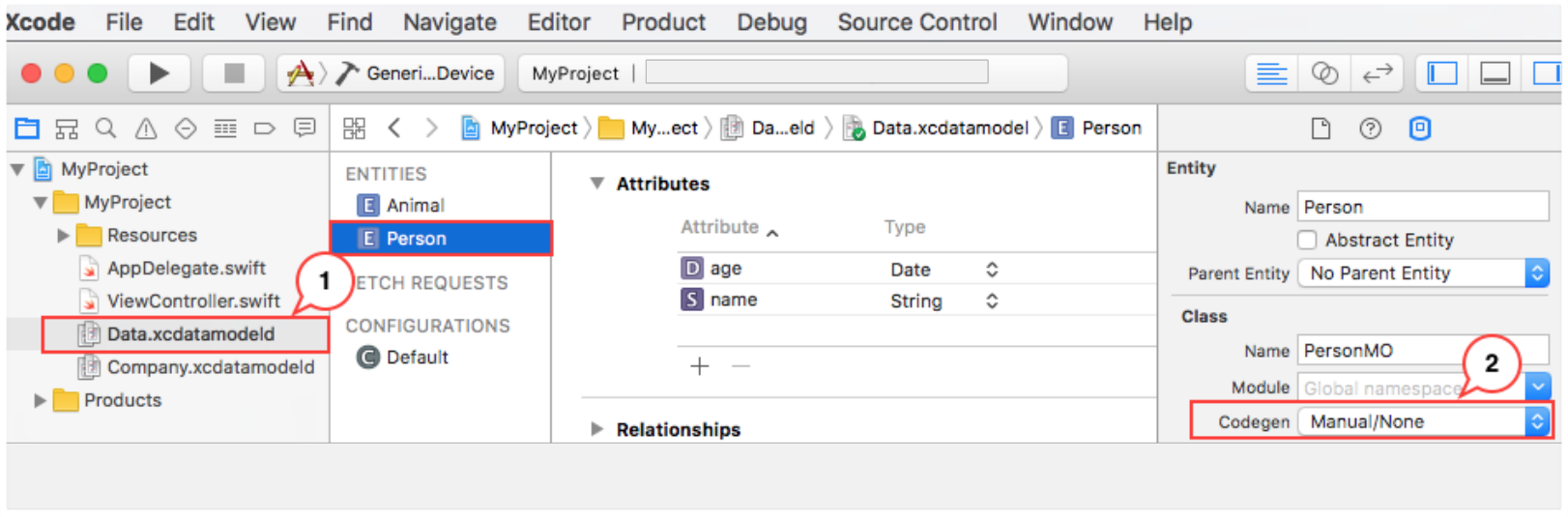

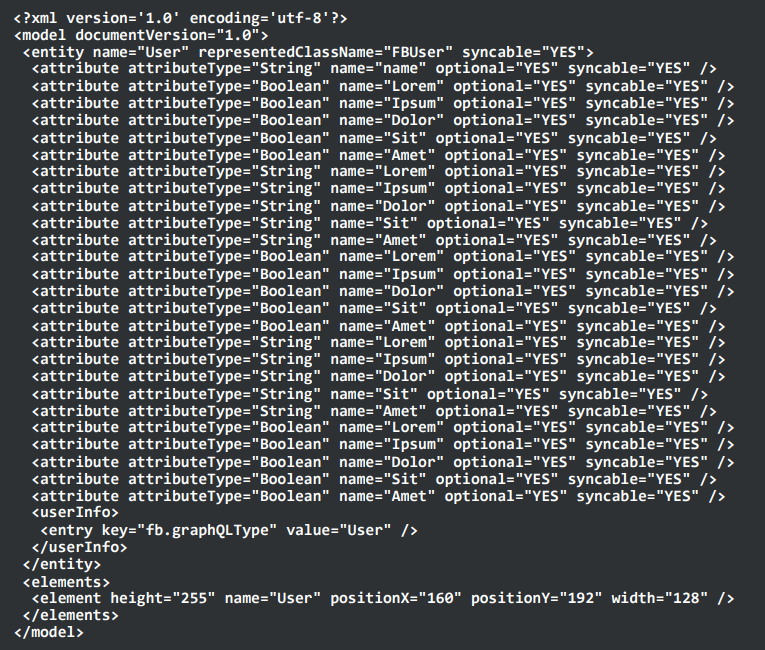

}Initially, to create a new model, they had to open up XCode, wait for it to load, click a lot of buttons, all to produce a giant indecipherable Core Data XML file.

This seemed like more trouble than necessary. Their input was just a GraphQL schema and the output was an XML file. This seemed like something you ought to be able to do on the command line.

CoreData XML files were a pain:

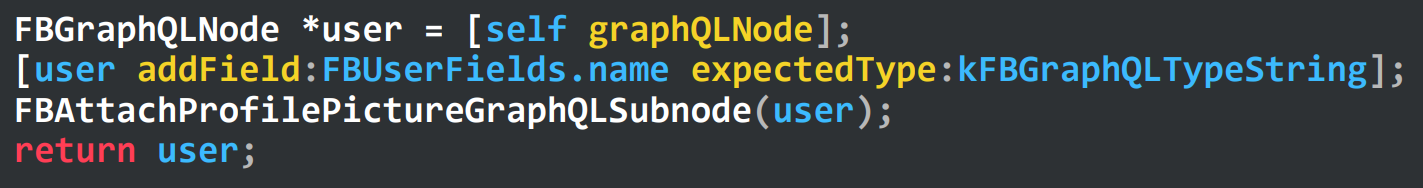

Their solution was codegen. codegen takes a GraphQL snippet in and outputs an XML file.

In order to make full use of codegen, they needed to create static GraphQL queries they could feed into codegen. These static queries were stored in .graphql files. But this presented a problem for code reuse. As more logic moved into .graphql files, GraphQL didn't have an easy way to reuse common code. The answer today to this problem is fragments. But at the time, they didn't exist.

Here's a quick refresher on fragments as they exist today:

query {

me {

name

profilePicture {

width

height

url

}

}

}becomes:

query {

me {

name

...ProfilePicture

}

}

fragment ProfilePicture on User {

profilePicture {

height

width

uri

}

}So they added fragments to address the code reuse problem. How did they implement fragments? They started with the client, not the server. They tested out the syntax and once they were happy with that, they implemented them on the server. The full implementation of fragments took 4 months, but they were able to validate the value much more quickly by starting on the client.

Scaling views

In the beginning, they had CoreData XML files for views. These have some obvious shortcomings.

Meanwhile they were moving away from Model-View-Controller and Core Data. They were moving toward more opinionated view frameworks, moving toward a one-way data flow architecture that eventually became Flux.

Over time, more view layout and logic was converted from CoreData XML into ComponentKit, a React-inspired framework for iOS and Litho for Android.

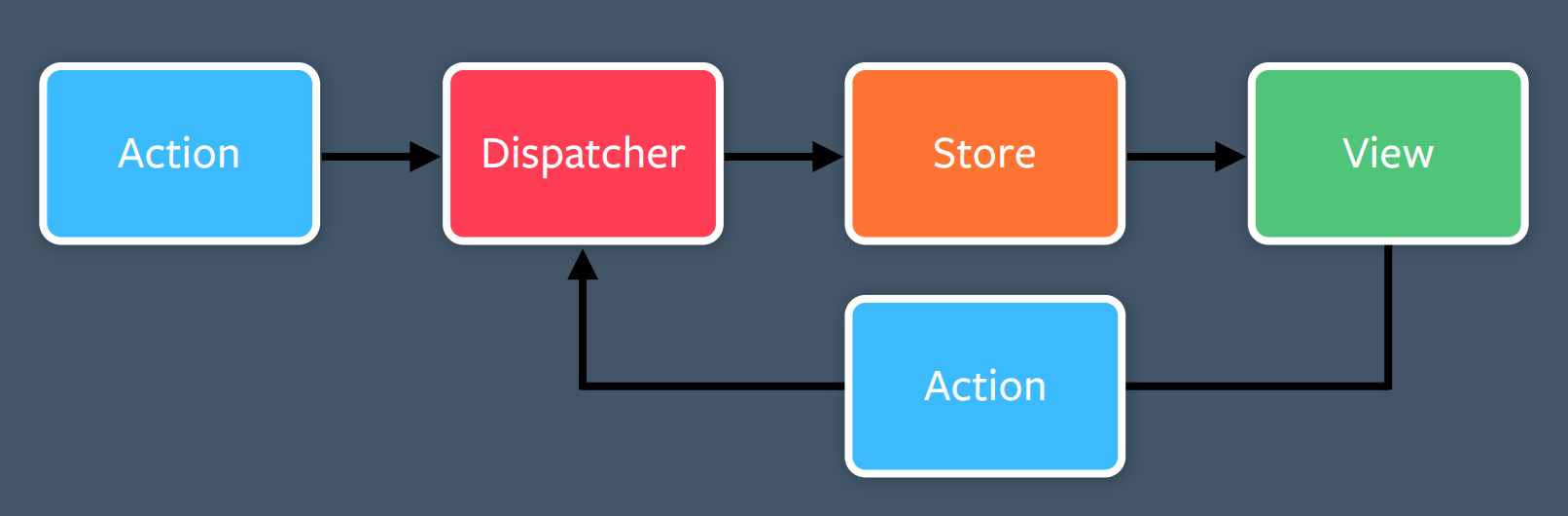

Here's the obligatory Flux architecture diagram.

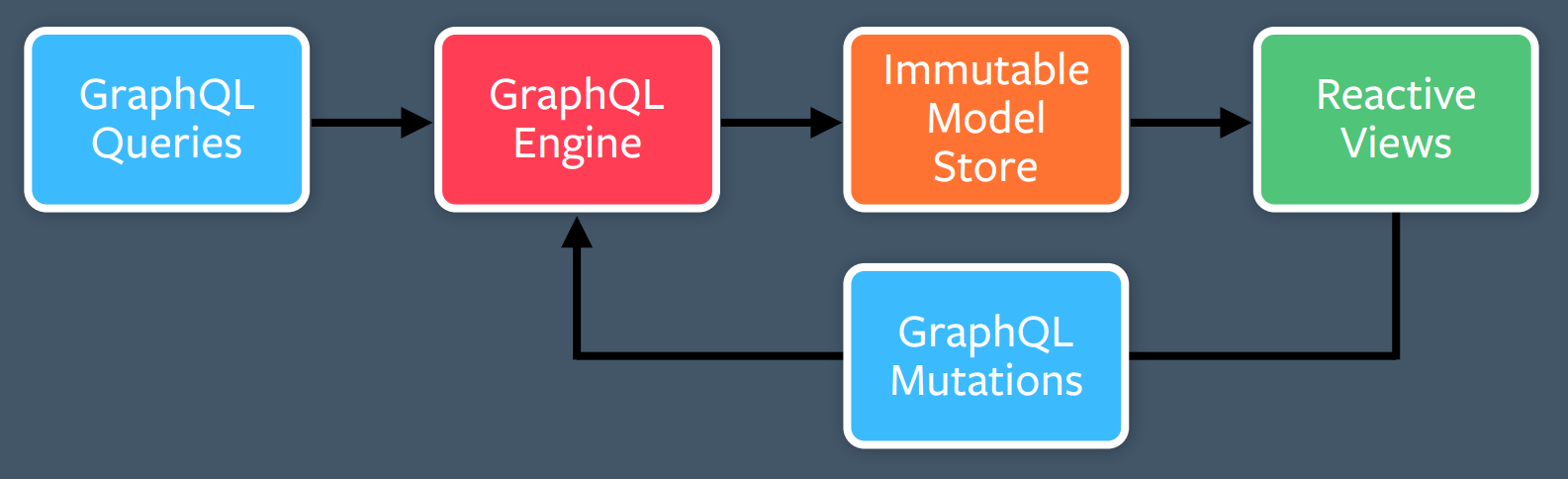

GraphQL fit neatly into a lot of these boxes:

But initially, they didn't have anything to fill in for the "Actions" box. The filler for this box eventually became GraphQL Mutations. So Flux really begat GraphQL Mutations.

When mutations were first proposed, they raised a lot of questions. Why top level mutations? Why not a special field on "User" that allows a rename? Why require a top-level rename? Why actions not CRUD?

The answer ties back to the Flux architecture and its one-way data flow philosophy. In fact, they probably misnamed it. It probably should have been "GraphQL Actions" rather than "GraphQL mutations".

Adding mutations to GraphQL wasn't obviously right at the time. People pointed out it's called "Graph Query Language" not "Graph Mutation Language". But they were driven by the needs of the client, so they added mutations to GraphQL.

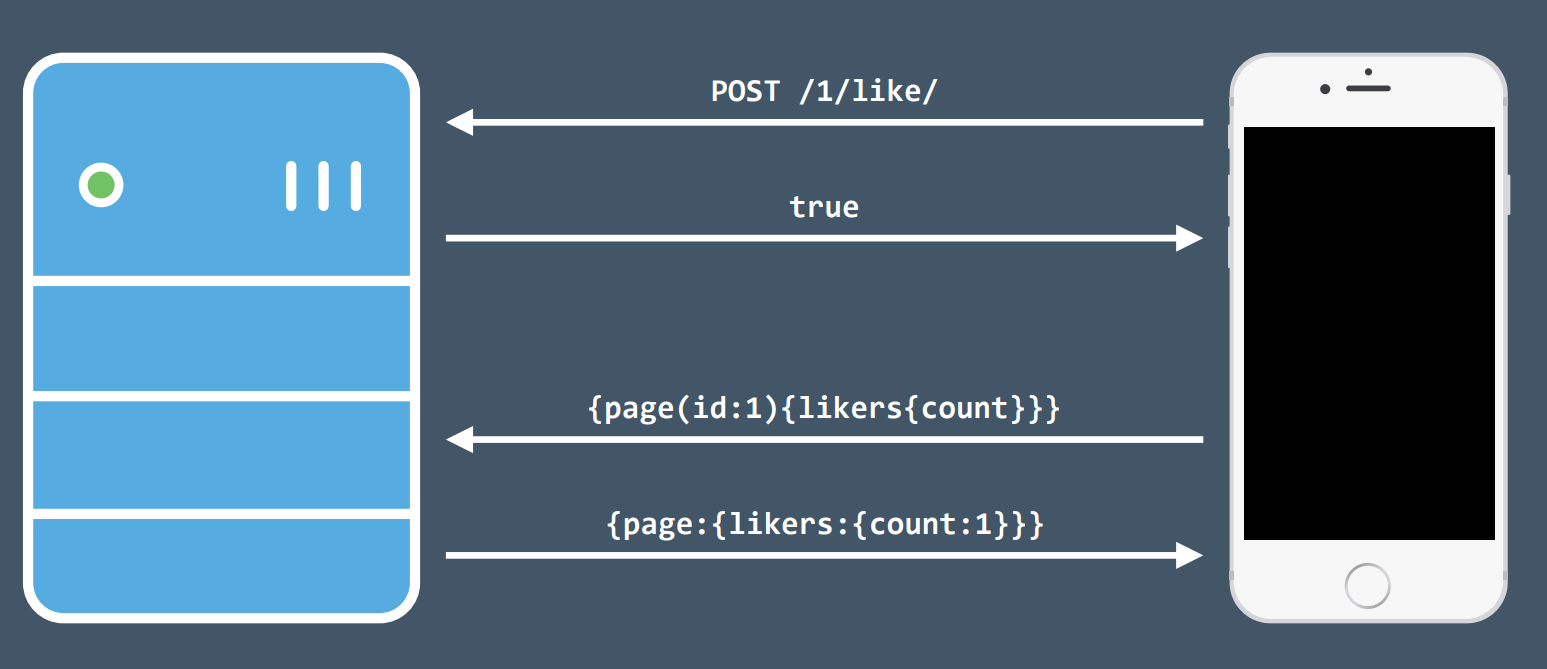

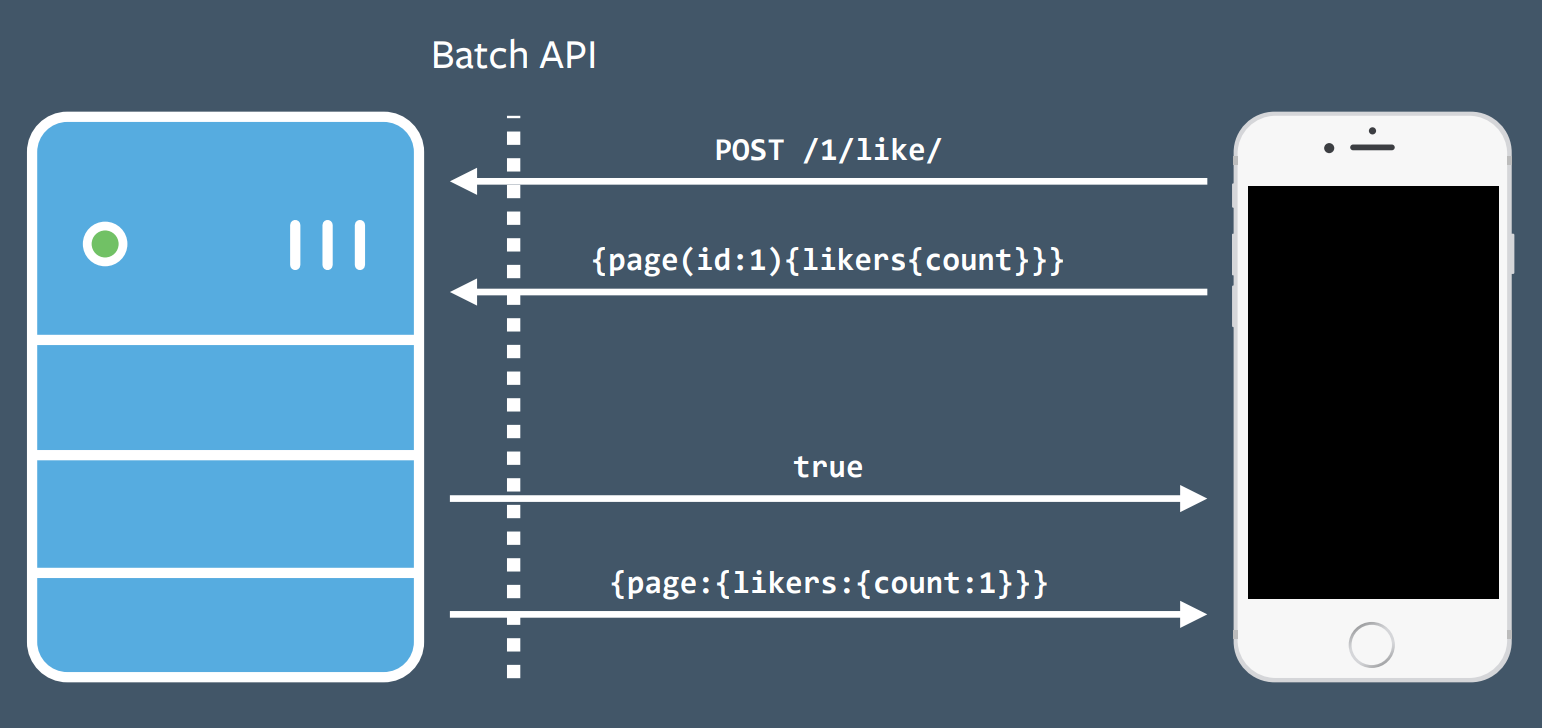

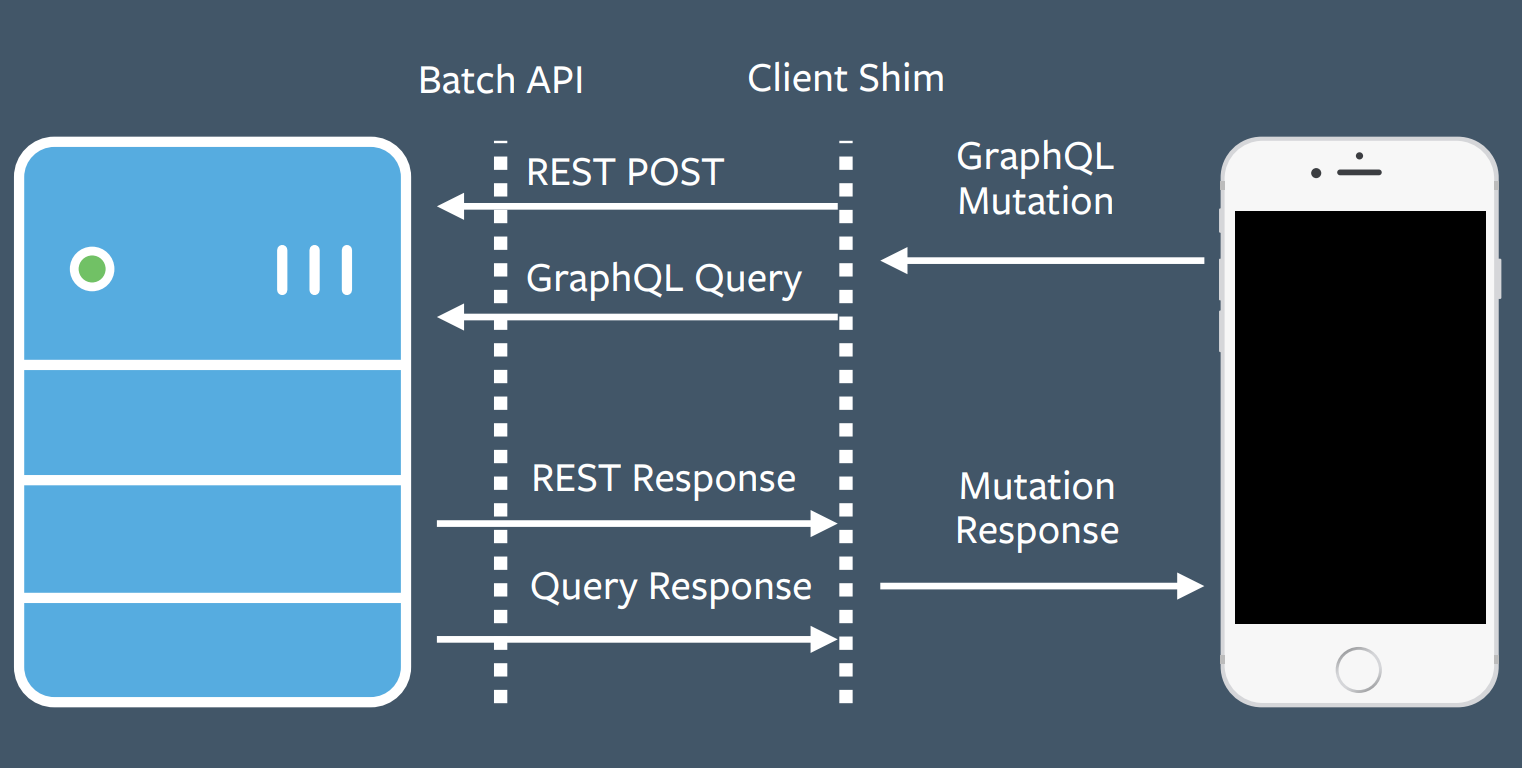

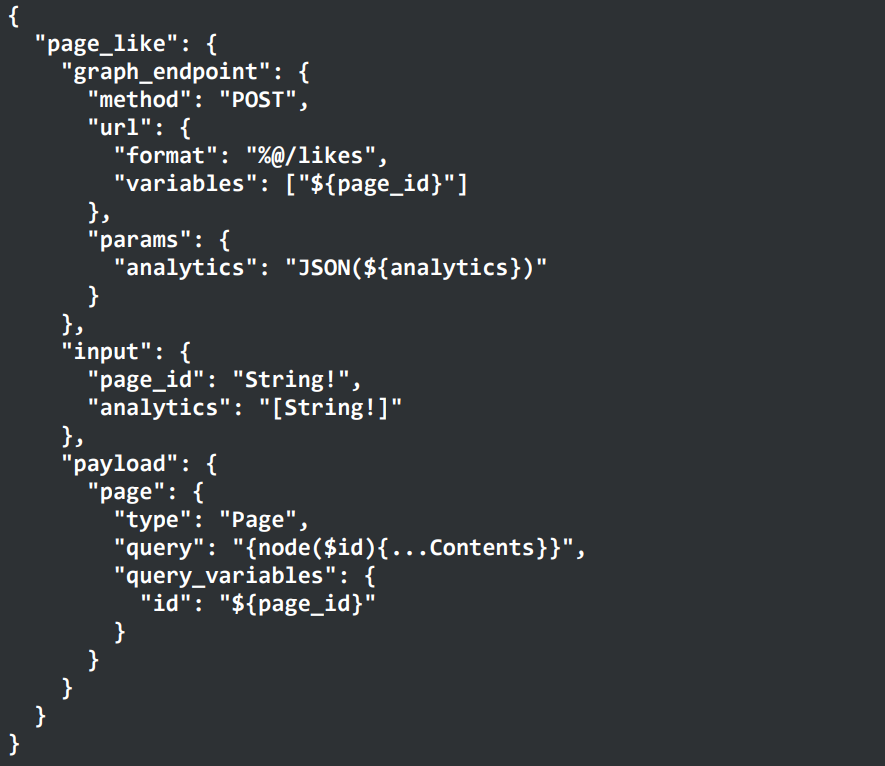

Once they decided that mutations would be valuable, they had to determine how to implement it. They realized there would be many ways to get it wrong. Again, they didn't start with the server-side implementation, but instead started on the client and created an implementation as simple as possible to demonstrate the value to clients. An existing common code pattern at Facebook was making a REST POST to execute a mutation, throwing away the POST response, and instead using a GraphQL query to fetch the data desired. The would result in an extra round-trip, so developers abused the batch API to do all of this in one round trip. They added a GraphQL mutations shim in the middle as an initial implementation.

They decided to piggyback on this pattern and added a shim that exposed a GraphQL mutation interface to clients while translating this to a REST POST request and GraphQL query on the backend.

Again, this client-driven development allowed them to quickly get a v1 version of mutations out to clients who could then try it and see the value. They later followed up with a more principled server-side implementation.

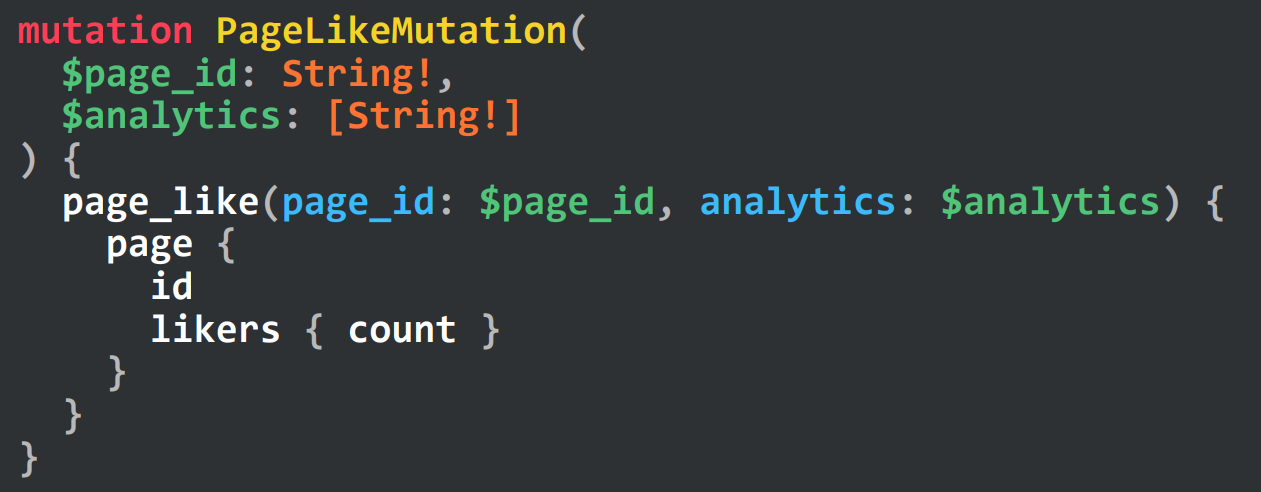

Here's what the mutation syntax ended up looking like:

Along the way, they added the ability to define reusable mutations:

The v1 mutations were made available in Oct 2013, but it wasn't until March 2014 that they merged a full server-side implementation.

Scaling updates

He's not going to go into great detail here, as there are two other talks that will deep-dive into subscriptions and live updates.

He'll focus on one aspect of subscriptions, the initial implementation of subscriptions. This exemplifies the client-driven development model he's talking about today.

Before subscriptions, clients had to repeatedly poll the API server for live-updating data. The API server would then have to repeatedly poll the underlying database, as well. This was annoying and very inefficient.

They needed to implement pub-sub on their API server. The "right" way to do this would be to add a pub-sub system on the backend. But this would take more time, so instead of doing this, their initial implementation was to hack around their existing caching layer and turn it into a pub-sub system. This allowed them to quickly provide the right interface to the client and prove it was useful. After the v0 was successful, they then went back and implemented a "real" pub sub system and hooked it up to their API server.

Future of GraphQL

This brings up right up to the open-sourcing of GraphQL in July 2015.

What does the future bring? He thinks directives will play a key role in enabling testing out new experimental features.

Directives were initially created to enable conditional field fetching. Suppose you want to fetch a user's nickname only if the it's in the nickname test group. Previously, you had to write:

query {

me {

name

nickname

}

}But they had a client that really wanted to do something like this:

query {

me {

name

nickname(if: $in_nickname_test)

}

}The above is what the syntax looked like for 3 years, but when they went to codify it, they realized it didn't really feel right. The conditional didn't seem like a true "field." So they added the directive syntax:

query {

me {

name

nickname @include(if: $in_nickname_test)

}

}In the future, they hope directives will allow creation and testing of more experimental features. It is a way to keep evolving GraphQL. GraphQL is not static and it's never going to be done.

Seeing the evolution from inception in 2012 all the way to today, there's no way they could have foreseen where it is today. They weren't sure it would be used much inside Facebook, much less be a massively successful open source project. So it's hard for him to forecast what GraphQL will look like in another 5 years. But he does believe that one thing will be the same: it'll still be Client-Driven Development.