GopherCon 2019 - Death by three thousand timers: Streaming video-on-demand for Cable TV

Larry Clapp for the Gophercon Liveblog

Presenter: Chris Hines

Liveblogger: Larry Clapp, @readcodesing

Overview

Can Go handle soft real-time applications? Learn about the challenges my team overcame to deliver video-on-demand MPEG streams to millions of cable TV customers using pure Go. Along the way we'll dig deeper into how Go manages timers and goroutine scheduling.

Chris @chris_csguy is a Principal Engineer at Comcast and has been doing Go since 2014. He's contributed to Go Kit and Go itself, and is a meetup organizer.

This will basically be an experience report from their project, using Go to stream video at Comcast. Despite the title, there's no actual death involved!

Agenda

- Video On Demand (VOD) Basics

- Performance Requirements

- Implementation experience

- The Go scheduler and timers

- Improving efficiency

- Results

- Looking ahead

VOD Basics

We've all used it: you choose what you want to watch, you press play, and you get your show. But lots going on under the covers.

There are several ways to do VOD:

- Direct download

- Progressive download -- starts showing as soon as you have enough in the buffer. Buffer runs dry leads to the dreaded ---BUFFERING--- ...

- Adaptive streaming -- can lead to pixelated video during low bandwidth

- Streaming -- ship the data as fast as you can. Need a reliable network. In the cable industry, they can control the network, so that's what they use.

Constraints

- Tiny buffers on set-top boxes, client-side

- Accurate and stable delivery rate. With small buffers, if you don't deliver fast enough, the video stops. If you go too fast, and you're using udp, the data's just dropped.

- Scalable -- lots of customers. Peak usage ~1M VOD sessions simultaneous across their footprint.

Today we're talking about the part of the process called the pump. It runs on "real hardware", not in the cloud. It reads from a local cache (which reads from an internal CDN (content delivery network)), and sends to the network. It reads from the cache in ~1M chunks via http requests.

So the pump takes the 1M chunks of data and chops it up and sends it out.

Performance Requirements

Hardware

- Bare metal

- 56 CPU's (28 hyperthreaded cores)

Target Capacity

- Max video output / server: 16 Gbps

- Typical stream bitrate: 4.5 Mbps

- Max concurrent streams / server: 3,500

Packet Sizes

- Ethernet MTU: 1,500 bytes

- MPEG-TS packet: 188 bytes

- Seven MPEG-TS packets: 1,316 bytes

So the pump groups 7 188-byte MPEG-TS packets into single 1,316 byte UDP packets.

Single Stream Packet Rates

- 427 UDP packets/s

- One UDP packet every 2.34 milliseconds

That's pretty close tolerances.

Single CPU Packet Rates

- 63 streams per CPU

- 27,000 UDP packets/s

- One UDP packet every 37 µs

So ya gotta be punctual!

Implementation Experience

Initial transmitter algorithm

Start simple!

- One goroutine per stream

- One rate limiter per stream: don't send packets too quickly or too slowly.

- A time.Ticker for periodic wake-ups: wake up the goroutine periodically

- On wake-up: Send a packet if rate limit allows

With Go 1.9, had to run five pumps per server to handle full capacity.

This scaled well horizontally.

But ... didn't really dig into why they needed five pumps. This becomes important later.

Later upgraded to Go 1.11. Skipped 1.10. So upgraded to 1.11, started load testing, and hit a snag. The same code built with 1.11 used more CPU than when built with 1.9. They were already at capacity, so that was bad.

So they went immediately to pprof, as one does. (Pprof is the Go profiling tool.)

Quickly found that runtime.findrunnable (and the things it calls) was using

2x the CPU in 1.11 as compared to 1.9.

Dug into the commits to runtime package since 1.9. Found a likely looking commit called

"runtime: improve timers scalability on multi-CPU systems".

Well their scalability hadn't improved. What gives?

Time to do some digging into the Go scheduler

The Go Scheduler

[What followed was a lengthy explanation of the Go scheduler and how it interacted with their code.]

At the root of it was that when you start a new goroutine, when it has to

start a new thread, the thread calls findrunnable to find a goroutine to run

on the thread. (findrunnable is the thing using so much more CPU time than

before.)

findrunnable can perform a process called "work stealing", which looks in

other threads' run queues for runnable goroutines. Since scheduling is a very

dynamic process, if it doesn't find anything, it does that three times in a

row, in case something new popped up on one runq while it was searching in

another runq. On the fourth pass, it'll look elsewhere, in other threads'

"runnext" slot, and (if no other goroutines exist) finally steal that

goroutine from that other thread.

So what happens if you're trying to start lots of goroutines? In general you get as many goroutines as you have threads pretty quickly.

The Go Scheduler and Timers

Go has a timer queue. This is where goroutines go to sleep. Go 1.9 has a single timer queue. (That's foreshadowing, haha.)

So a goroutine calls time.Sleep() for 1s. It goes into the timer queue, and

Go starts a special goroutine called the timerproc. The only way it's special

is that the runtime starts it; other than that it's a regular goroutine, and

gets scheduled (or not) like any other. Its job is to wait for timers to

expire and do whatever's supposed to come after that, typically waking up a

goroutine. It does that by using an OS primitive to sleep until the very next

timer needs to wake up, and then proceeding. To sleep, you need a thread, so

it creates a thread to sleep in.

And then there's a bit of a dance when goroutines go to sleep and wake back up again, but generally things work pretty well. In particular, Go is pretty good at not having threads sleeping when there are goroutines available that want to do work, which apparently some other language aren't as good at.

So back to that commit we talked about ...

"runtime: improve timers scalability on multi-CPU systems"

What'd they do? They sharded the timer queue. In 1.11 - 1.13 there are timer queues == GOMAXPROCS. Which helps scalability, since the timer queue has a lock on it. So if you have lots of threads sleeping, you have lots of contention for that lock. So by making several queues, there's less lock contention.

So why did that result in more CPU used?

They thought, We can go to sleep faster, but that means that more threads are doing work stealing (which can use CPU time), so maybe that's what's happening?

Scheduler Observations

- It's good at quickly finding a new goroutine to run

- It's good at keeping available CPU's busy

- It burns CPU proportional to GOMAXPROCS in work stealing when run queues are empty

- Waking from a timer takes multiple context switches on OS threads, which isn't cheap.

The Go 1.11 Timer Optimization

- Reduced lock contention

- Let goroutines go to sleep faster

- So threads do more work stealing

So this actually helped them to understand why they needed five pumps on a server:

- Running 5 pumps was their way of reducing lock contention in Go 1.9. They'd essentially emulated Go 1.11's multiple timer queues.

- But they still had GOMAXPROCS = 56, which was actually too many.

- Which made Go 1.11 slower than necessary, because they were doing more work stealing on a bigger pool of processes.

So they tried GOMAXPROCS = 56/5 = 12. PAR-TAY. CPU usage in 1.11 actually dropped below 1.9.

So immediate problem solved. Yay.

But still curious as to root cause. So they filed an issue with the Go project. Description, example code, pprof output, and so on.

First suggestion was: Try just one pump?

But they tried that and it didn't work.

But ... why not?

(And this was all spread out over months. Lots of experimentation and exploring and thinking.)

Improving Efficiency

In a single stream, ideally, they send a packet, which takes 0.01ms, and then sleep for 2.34ms. That's a lot of intervening time. Which is good, because they service lots of other streams in that time. But all that sending happens more or less at random. So all the "not-sending" is sleeping. So they have lots of little sleeps. Which means lots of work stealing. Which means lots of context switching to wake up. And that's lots of CPU for nothing.

So how could they sleep less? What if they could group all that more-or-less random sending into chunks, back to back, so they wouldn't have to sleep?

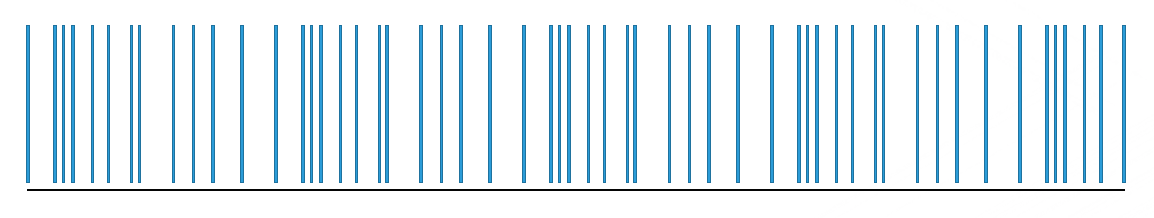

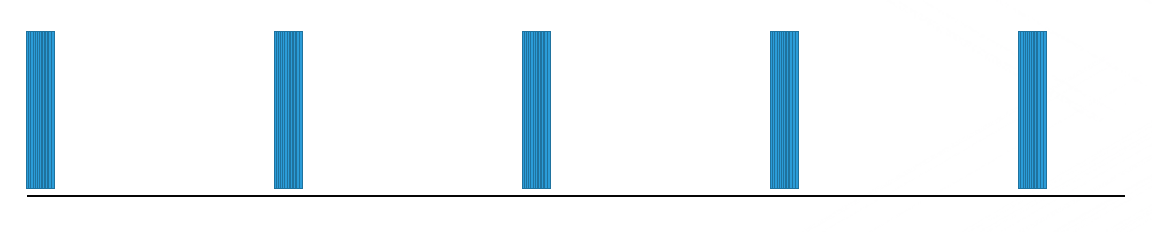

What if they could change this

into this?

Fewer sleeps, less work stealing, fewer context switching to wake up, and (hopefully) less CPU for the same work.

Two Prototypes

So they tried two prototypes. The first led to the second:

- Serve multiple streams with a single goroutine (stream multiplexing)

- Something so crazy, it just might work

Stream Multiplexing

Create GOMAXPROCS packet scheduler goroutines. Each requests a time range to send their next packet. Find a bunch of packets in the same range. Send them out all at once without sleeping. Sleep until the next group needs to go out.

BUT THEN ...

If their goal was just to get everything grouped in time ... what if they just woke up all the goroutines at the same time?

Just round off all the sleeps so all the goroutines wake up at the same time, so when timerproc wakes up it finds a whole bunch of goroutines ready to run at the same time, and dumps them all into the run queue, without sleeping. Let Go do its thing.

Results

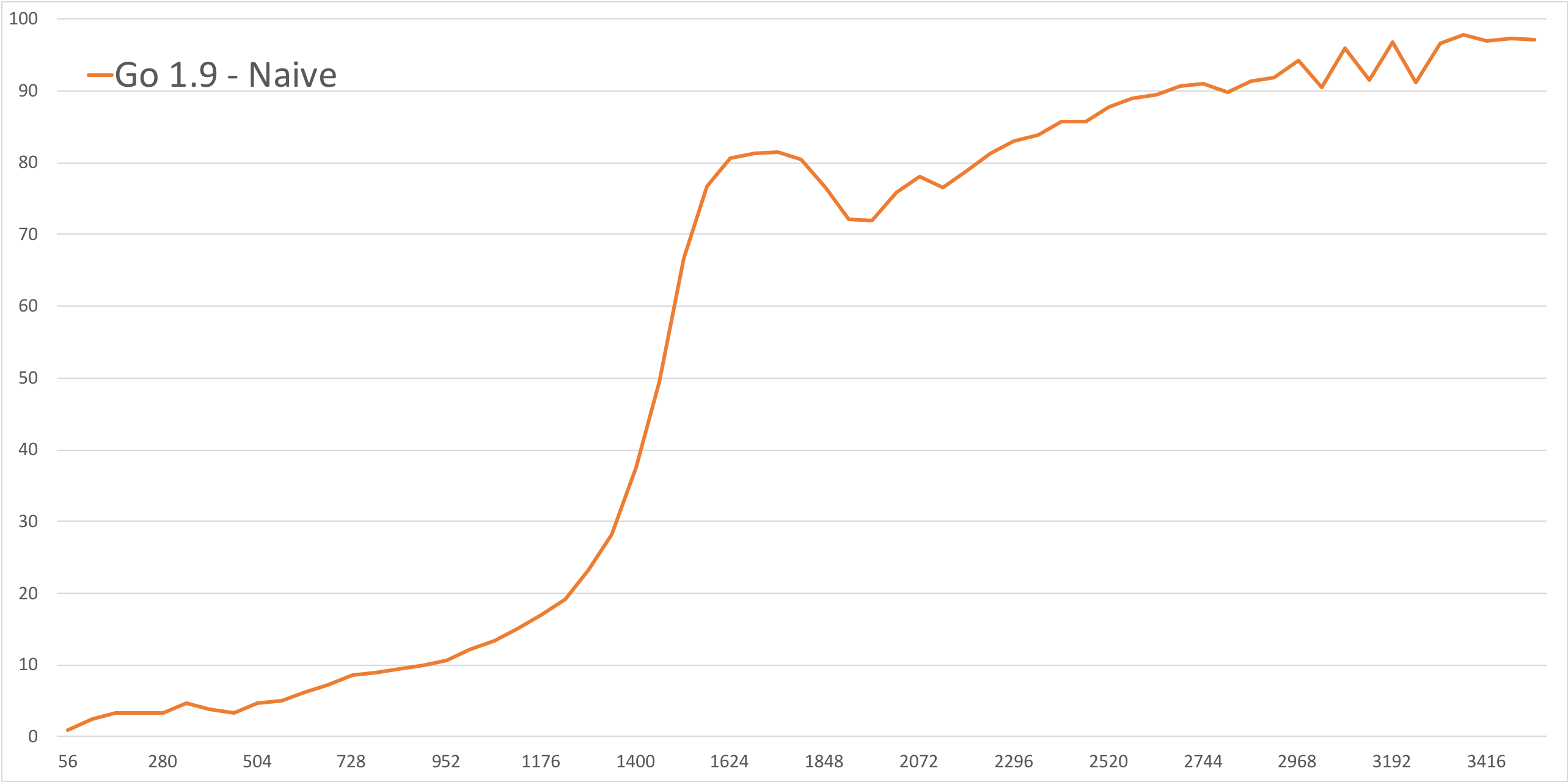

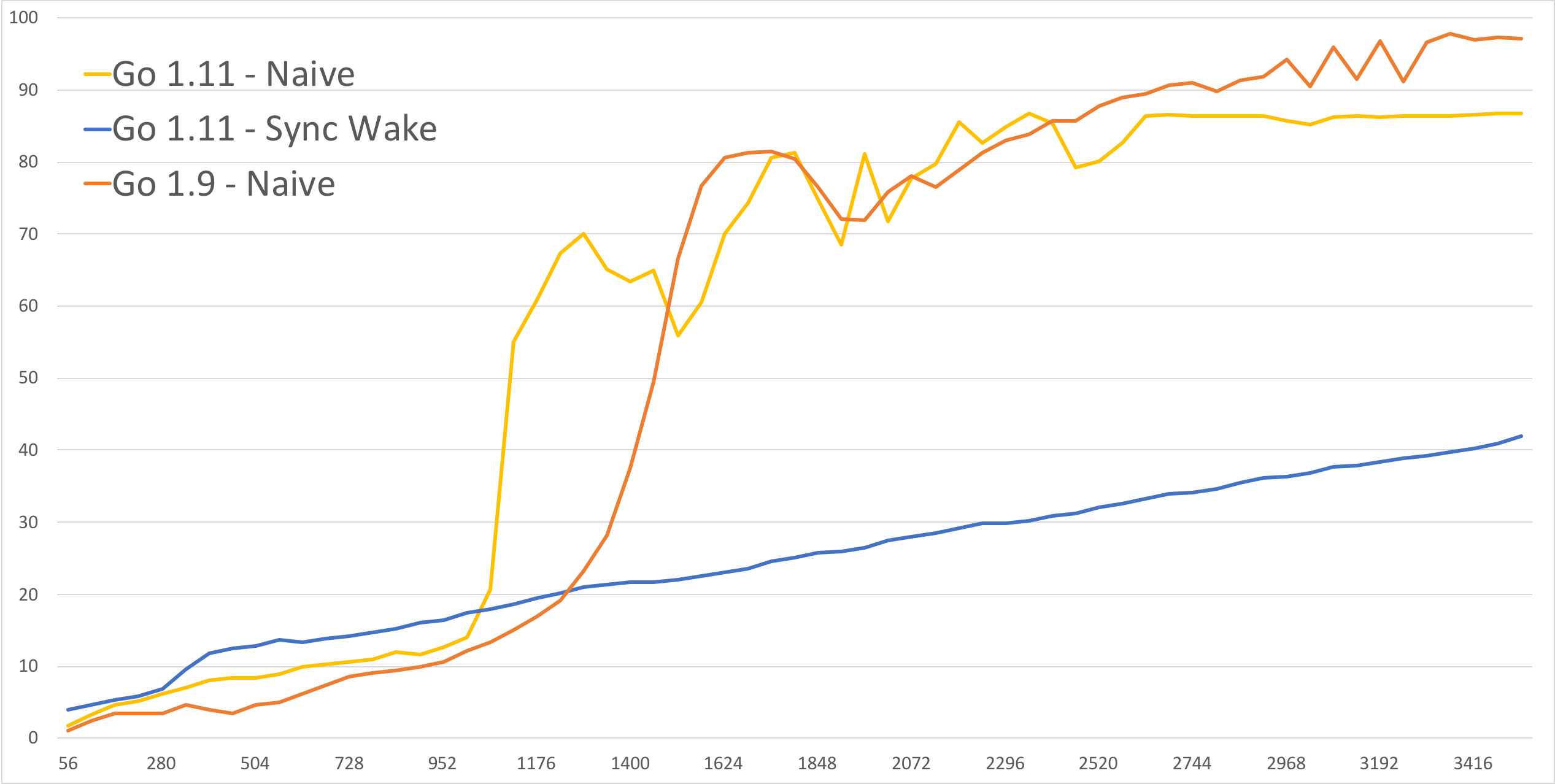

This is their initial cpu usage graph. Bottom axis is # of streams, and left axis is CPU usage as reported by the os. Note the "hockey stick" starting about a third of the way across the graph.

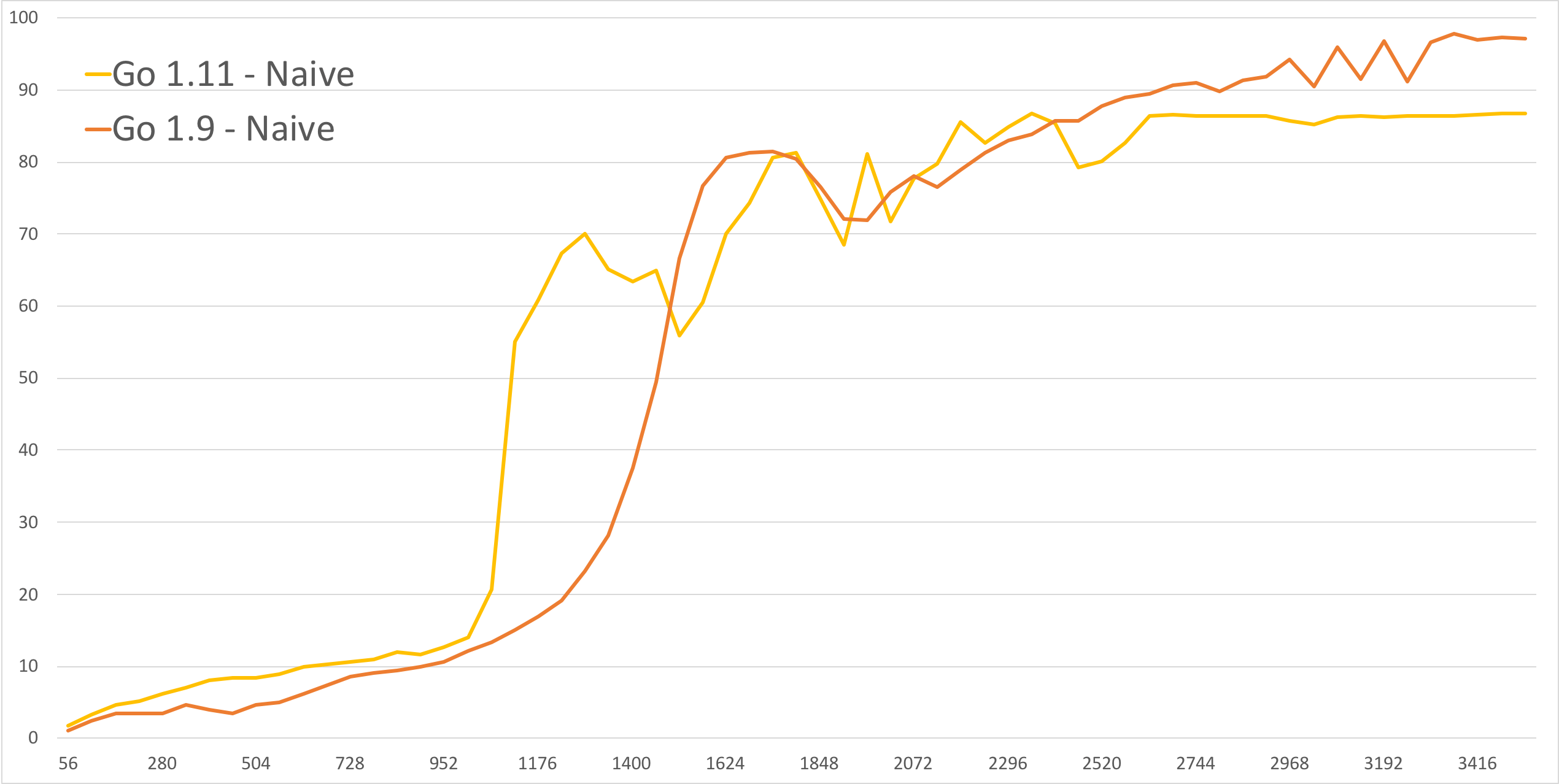

This was the same code after switching to Go 1.11. Before the hockey stick the graph is higher (more CPU) and the hockey stick starts sooner.

Implementing the synchronized wake-up took 15 minutes; it was literally a

one-line change: add time.Truncate() to the wake-up time.

So now there's no hockey stick behavior, and it does a much better job on the high end. Weirdly, on the left, it's worse, which was surprising, and they don't know quite what that means. And there's that little hump on the left, too. ??? But shrug this is the real data.

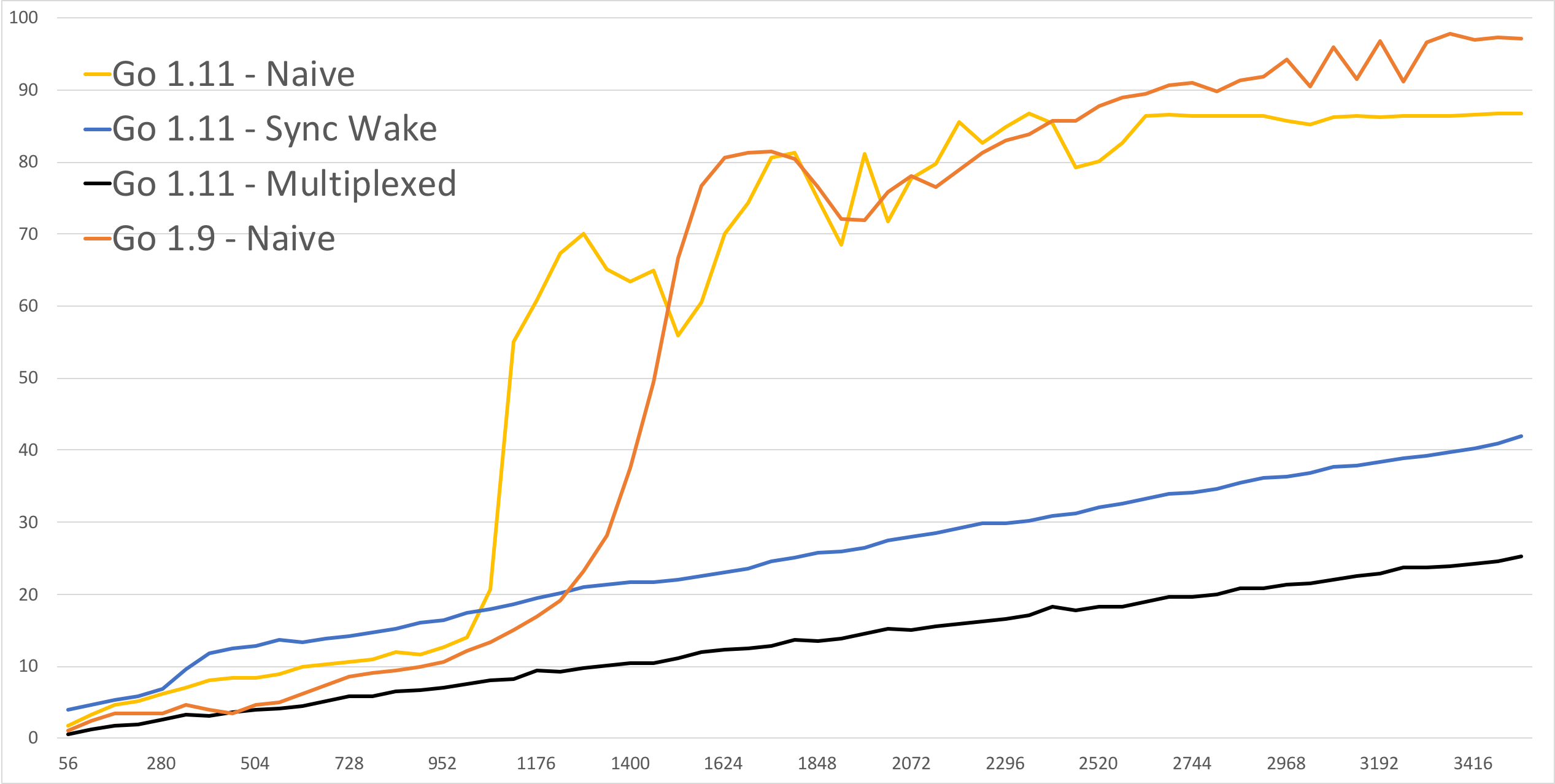

So anyway, then they got their multiplexed idea implemented, and they got this:

So now they're better everywhere, and they're nice and linear.

Pros and Cons

Multiplexing Pros

- More efficient for all stream counts.

- Packet delivery rate more consistent

- Handles mixed bitrates well

Cons

- Adds complexity. They're basically writing a custom scheduler on top of the regular Go scheduler. It's not a lot of code, but it's not nothing.

- Code must not block on the packet delivery path. Writing non-blocking code in Go can be tricky.

Crazy Idea Pros

- Simplicity — one line change

- Code can block if it wants, just like any other Go code

- Scales pretty well within a single pump instance

Cons

- Does not handle mixed bitrates gracefully, which they need.

- Less efficient for lower stream counts

So went forward with the multiplexing approach, since it was better on all measures. Except complexity. So they documented it and added unit tests.

Getting Production Ready

All that was in a prototype. Then it was time to integrate with their actual production code. Some hiccups there:

- Video stream input code was scheduler hostile too, but they fixed those pretty easily

- It took a few iterations to remove blocking code correctly, so e.g. one video stream getting data didn't interfere with another video stream.

But about two weeks ago they got this all working and into the QA environment, tried it with a completely cold cache, went to full load, and ...

They were at 40% CPU usage on the box at full load.

All the pumps, all the caching software, everything. It was great.

Looking ahead

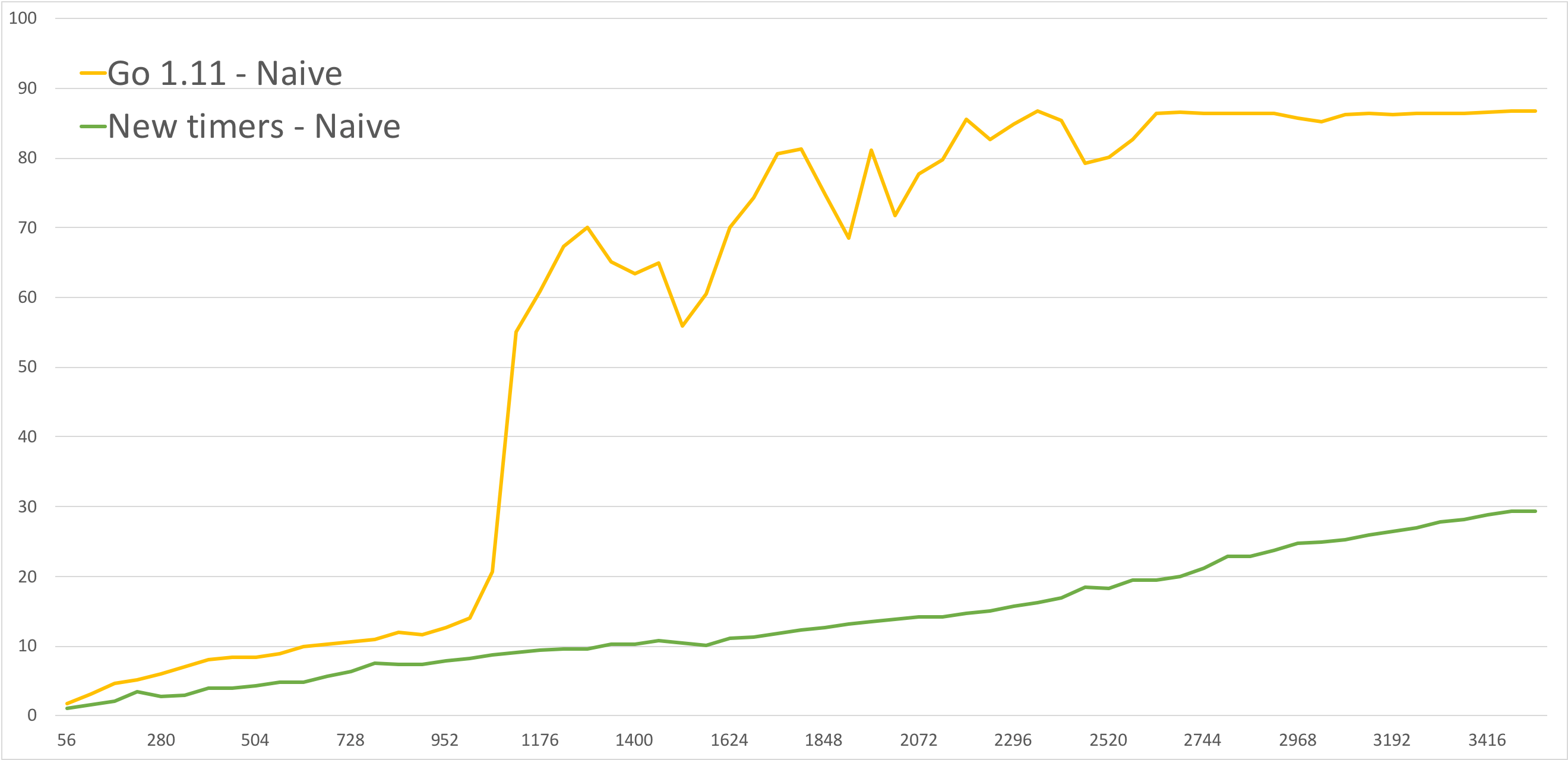

Ian Lance Taylor is rewriting timers, again. Argh. But they got their hands on that branch and tried it.

Go 1.14 Timers:

- Timers moved into the P struct, instead of being a separate thing

- No more timerproc

- Adds timer stealing to

findrunnable

Bottom line, it eliminates a lot of context switching when a goroutine wakes up.

The benchmark numbers at the end of Ian's commits are ridiculous. 95% improvement on some functions in the time package.

So they tried Ian's branch with their tool. Separate goroutines for every stream. The bad one is Go 1.11, and the bottom line is with Ian's new timers, without any special multiplexing on their side.

Has many of the properties of their multiplexed implementation, but if you look carefully it starts to bend a little upwards at the end.

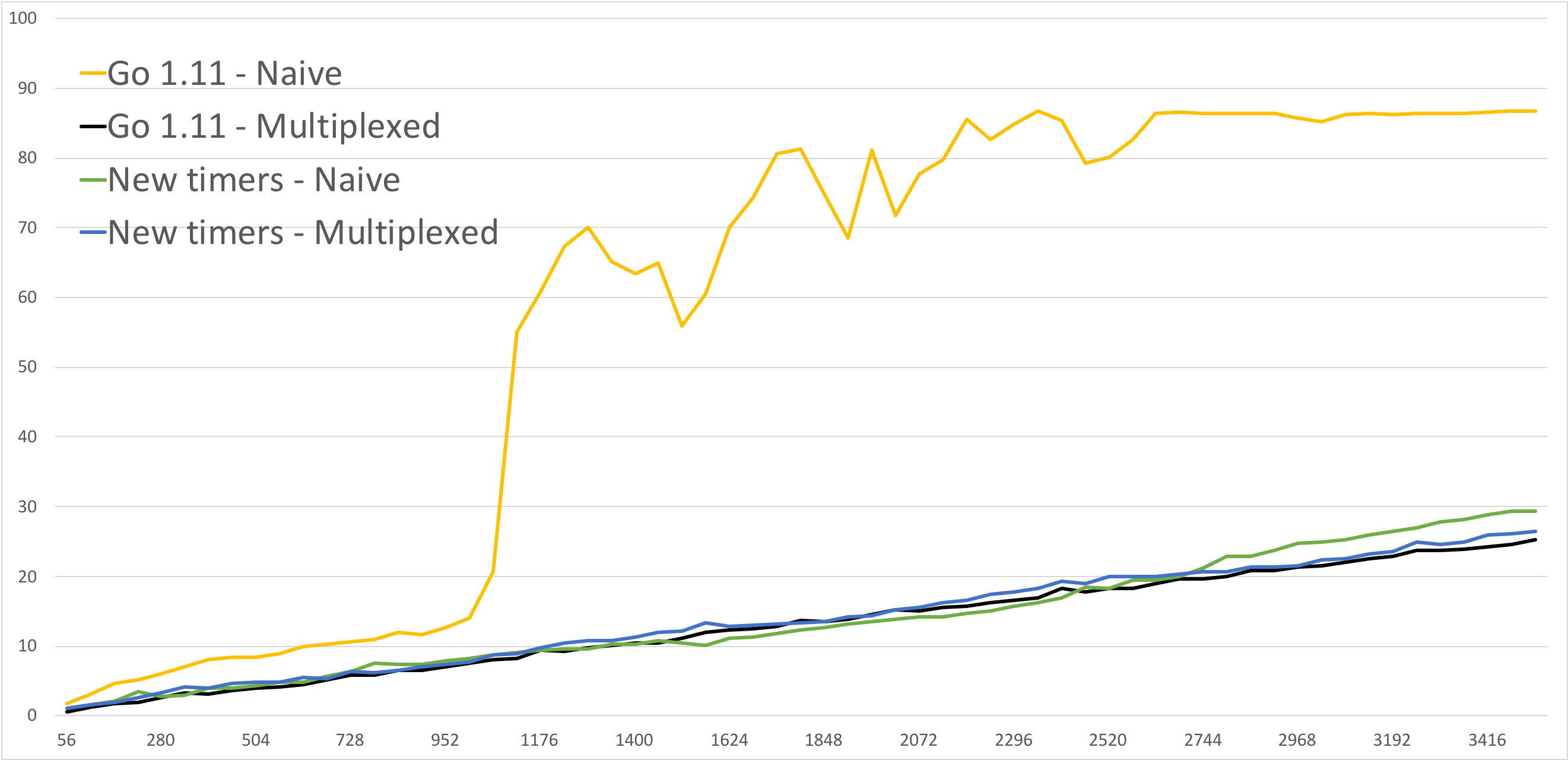

Here's their implementation, with the new timers, both "naive" and multiplexed. So theirs is a couple percentage points better, but it's mostly "in the noise".

So could they just throw away their multiplexing code when 1.14 comes out?

Maaaaybe. But their approach lets them use ipv4.WriteBatch, to send lots of

UDP packets with one system call (on Linux). An order-of-magnitude fewer

system calls sounds good to them! But they haven't tried it yet, so that's

upcoming.